8 May 2025, Leonda, Hawthorn, Melbourne, Australia

Somewhere, in the back of my mind, I’ve wondered where I might be when the terrible day arrived. I would never have guessed 16000 kilometres away in an Airbnb in Budapest, barely awake but already trying to share a Dave Barry article about his prostate on the family group chat. It was Dad who called, dialing my phone number that has and always will end with Mum’s birthday 10.06.45, and I could tell by the tremor in his breathing that this was it. This was the day. I was cold all over before he started speaking: ‘Tony, I’m so sorry I have to tell you this but your mother, your beautiful mum who we’ve all loved so much, died today.’

Two hours later, Polly and I were in the square in front of St Stephens when the bells started ringing. We stepped into the middle of the square, and the bells just rang and rang and rang. We stood shoulder to shoulder, gazing up at this glorious cathedral, and the deafening cacophony didn’t let up. On and on it went. People began to assemble on the church steps, hundreds of people, but Polly and I didn’t move, squinting into the sun and the spires, faces flushed, tears streaming, and it all continued for nearly an hour. The bells of St Stephens, tolling for Mum.

Look it’s possible they were also tolling for the Pope, who died an hour earlier, but I’m going to say they were for Mum. And although none of us Wilsons are particularly religious, I did picture her at the gates of heaven, and I imagined a carnival atmosphere up there, just a great day to be at the pearly gates. And I thought two things. I thought firstly, there’s absolutely no way my beautiful, kind, generous mother isn’t getting into heaven. And secondly, I really hope she doesn’t let the Pope queue jump.

Of course Mum wouldn’t want me dwelling for too long at the gates of heaven in this eulogy. There’s a reason we’re at a reception centre and not a church. She was raised a North Balwyn Methodist, the eldest of five girls, and lived the tearaway social life you’d expect from North Balwyn Methodists in the 50s and early 60s. Even now, if an organist strays into this place and leans on the opening notes of ‘All People Who on Earth Do Dwell’, the three remaining Voutier girls will leap to their feet, ready for choral action. I’m not even ruling Mum out.

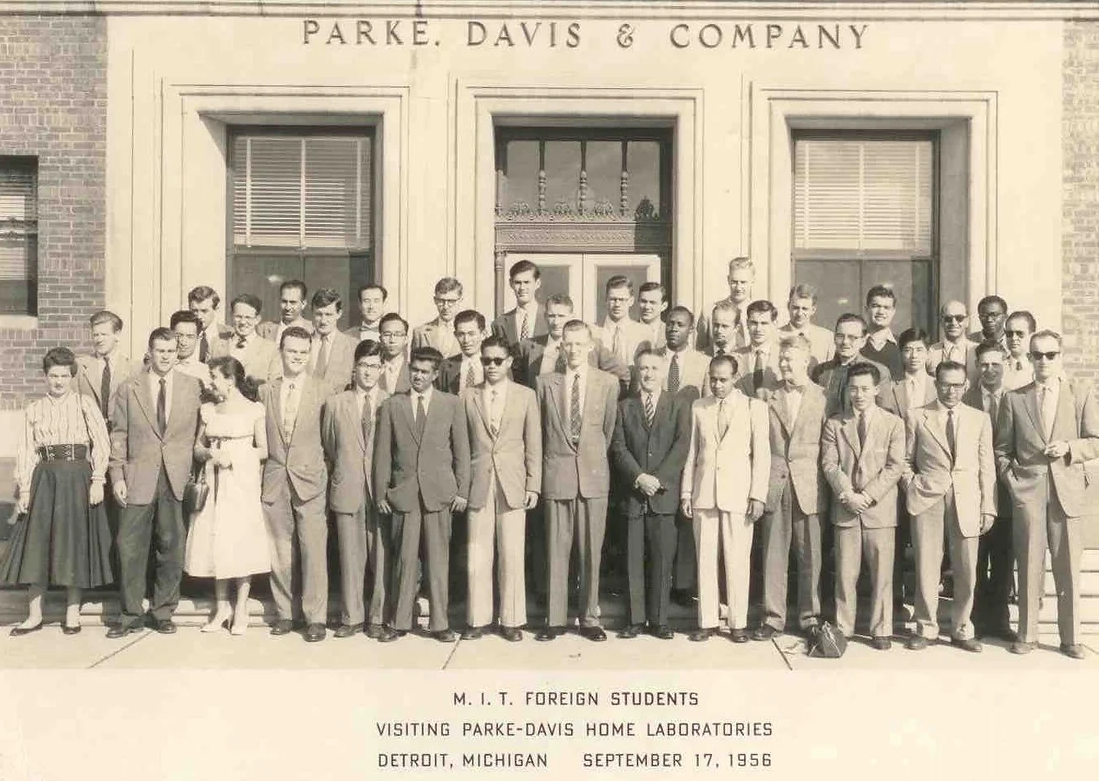

She was so smart, such an academic talent. In Year 7, she won a scholarship to MLC, but her father didn’t let her take it up because with four girls following, it might not be fair on everyone. Later, she graduated near the top of her class at Balwyn High, and went to Melbourne Uni to study Science and a Dip Ed. Teaching wasn’t her first choice, but her father again had strong views, this time that his daughters choose either nursing or teaching. These were the good jobs for girls, he reckoned, and that’s where the Commonwealth funded scholarships were too. Mum actually loved science, loved her science friends, although teaching not so much. A lot of the Year 12 boys at Benalla High asked her out during her teaching training year and she wasn’t a fan of that. She did courses throughout her life — computing courses in the early days of the Logo programming language, horticultural courses at Burnley, somehow fitting it all in between parenting four children. When she thought Sam’s Year 12 biology teacher was missing the mark, she purchased the first year uni text book and taught her the course herself. They got 100%. They got into medicine. Pippa did the same a few years later. Sam gave an amazing speech at Mum’s 75th birthday about women of Mum’s generation and the sacrifices they made. So much of her talent, her phenomenal talent, was lavished on us.

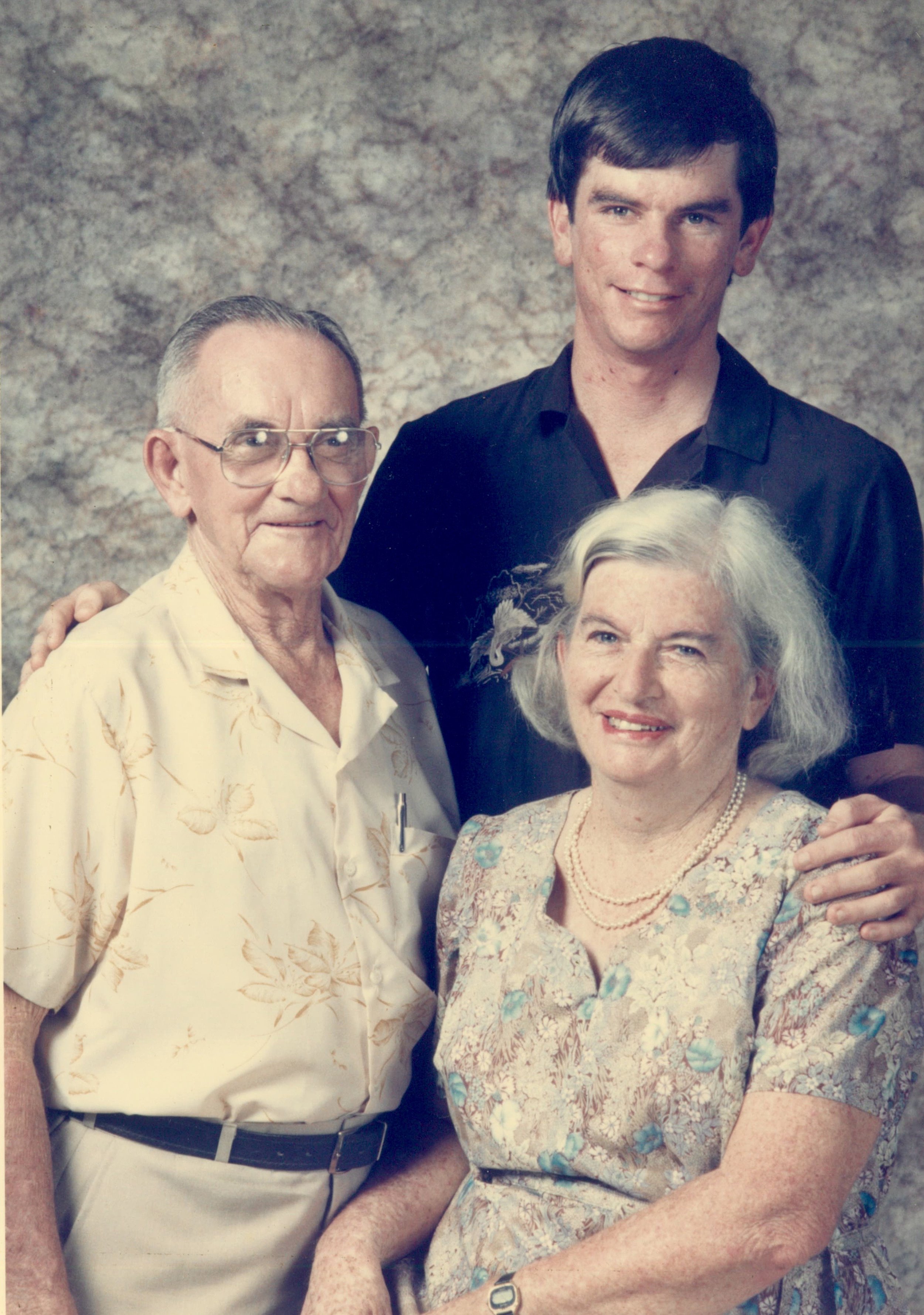

She was a spectacular beauty, and it’s been a running joke amongst her four children that her puny, pretty genes were no match for dad’s pale balding genetic headkickers. We don’t care though. Who wants to be a nine or a ten anyway? It’s character building down in the sixes and sevens. I for one can walk past any building site and nobody ever hassles me.

It also gave Mum things to work on. It was impossible to enter a room without her commenting on my appearance. ‘Do you want me to shave your neck, darling?’ ‘What are you taking for your face rash? Do you think it’s because you’re drinking milk? I think it might be the dairy. Look at your nails! You can’t let them get like that? Do you want me to cut them? Does Tam cut them for you?’

When I applied for Race Around the World in 1998, and made it to the finals, Mum had one of her greatest grooming masterstrokes. ‘I think you should tint your eyelashes’ she said. ‘It’ll work, I promise you, make your eyes seem bigger.’ A day or two later, I was in a salon — yes, we Wilson kids are nothing if not compliant — getting my lashes done. Six months later, me and my long irresistible lashes won Race Around the World. Was it all because of the eyelashes? Well we’ll never know, but, yes, yes Mum, it was.

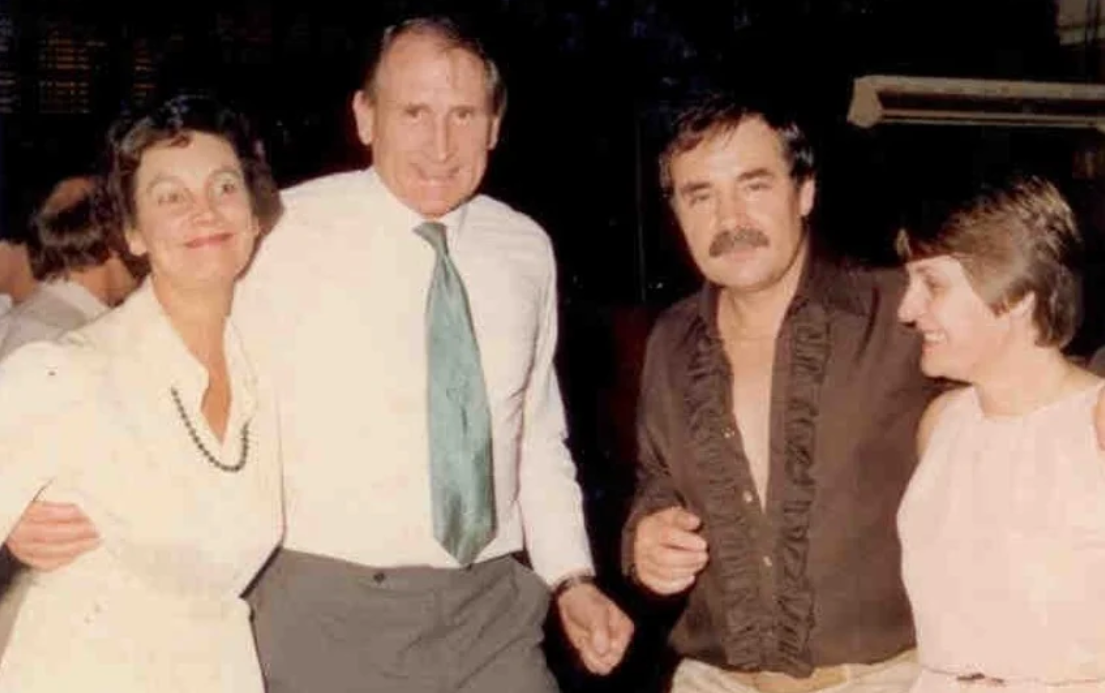

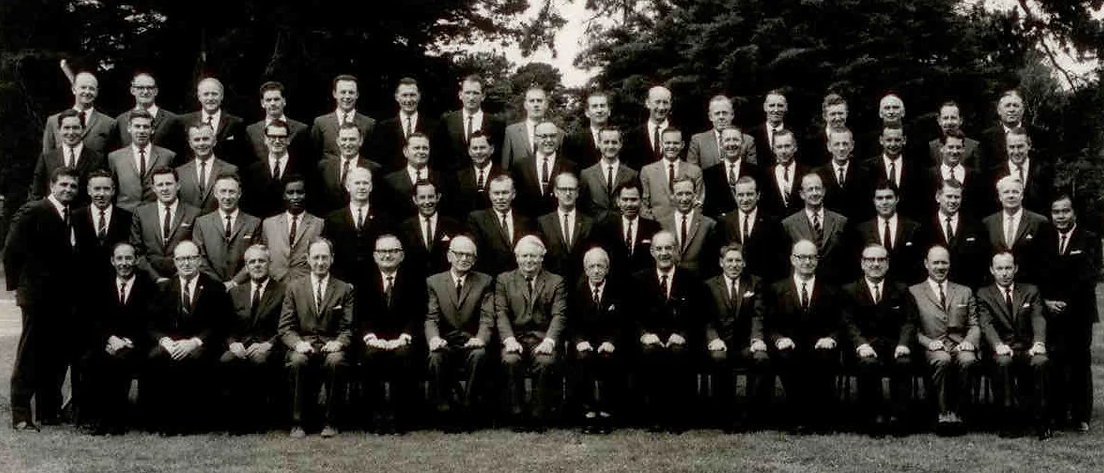

Mum had her own television moment three decades earlier. In 1969, Dad was playing league footy at Hawthorn and the Sporting Globe and Channel 7 had a Miss Footy competition. The idea was that wives and girlfriends were circled in the paper, and for that glory alone you won you $5, some Dr Scholl’s orthopaedic sandals, a Volutis perm styled by Lillian and Antonio, and dinner at the Southern Cross Hotel. It was also an entry ticket to the Miss Footy Trivia Quiz on Channel 7s World of Sport. Mum’s face got circled but she was initially indifferent. The truth was she already had a pair of orthopaedic sandals and knew absolutely nothing about footy — also, the prize the previous year had been a trip to Mildura.

It all changed though when details of the 1969 prize were released. It was an all-expenses trip to Japan and Hong Kong, staying at the five star Mandarin hotels. The total value of the trip was more than Dad’s annual salary as a teacher. They’d been married two years and neither of them had ever been overseas before.

And so Mum rote learned the history of football, basically the whole lot, from Brownlow Medallists to club theme songs, club presidents, everything. Dad was her tutor and put lists all over the house. I can’t imagine how exciting this must have been for him. His young, beautiful bride whispering John Coleman’s career goalkicking stats into his ear. Mum learned it all, of course she did, and breezed into the last eight, then the last four, only to play out two tense grand final draws with Lyn Grinlington, a young teenage Hawks fan who, unlike Mum, actually liked football. Their rivalry captured the sporting world in the spring of 1969. ‘Beauty and Brains too!’ is one article we have clipped from the Herald. Another went with ‘Quiz Cuties at it Again’. In the end, Mum was simply too good. The winning question was ‘Which Richmond premiership player before the war coached a different team to a premiership after the war?’ The answer I hear you screaming is — Checker Hughes. Mum knew it, Lyn didn’t, and finally, gloriously, they were off to Japan and Hong Kong. Second prize was $50 worth of hair care products.

Between 1971 and 1979 she had the four of us, and she lavished so much love in our direction, it’s really difficult to describe. But she was demanding too. I only have to say words like Suzuki method, and Montessori technique for you to get a bit of an idea. She also convinced pre school Samantha that frozen peas were lollies. Imagine Sam’s surprise when she went to her first birthday party in prep. When Mum picked her up, the host mum said to our Mum, ‘I’m worried she’s going to be sick. She’s had nine chocolate crackles’. Ah Sam. What a moment. It’s hard to go back to frozen peas after copher.

She was also fanatical about restricting television, ‘half an hour a day, that’s it, then homework or reading.’ It was an ongoing espionage battle. Ned was our sentry, listening for the crunch of tyres on gravel when she was coming back from the shops. Sometimes, like a secret agent, she’d attempt surprise attacks, parking down the street and then sprinting in to place hand or cheek again the back of the box to feel if it was warm. If the Stasi caught us watching more than Get Smart, we’d be banned from Get Smart the following night. There were no real winners in this war. When I think about it, it’s an utter disgrace how many series she binged over the last few years. I should at least once have hid outside in the bushes and then jumped out. ‘Mum, no more Bridgeton! Go read your novel!’

Mum didn’t need any motivation to read novels. She was such a prolific reader, the east Melbourne library was a favourite place of hers. Ticking as it did two crucial Margaret Wilson boxes – the ones marked ‘books’ and ‘thrift’.

As a child, she read us everything from Seven Little Australians to The Wind in the Willows to Tolkien. As a teen, she put me onto John Wyndham, Aldous Huxley, JD Salinger, Margaret Atwood, Eli Wiesel, Toni Morrison and Clive James. As an adult she fed me Kate Atkinson, Cormac McCarthy, Kate Grenville, Ann Pratchett, Geraldine Brooks, Christopher Koch, Jennifer Egan and David Mitchell. And so many more, of course. She was never without a book or a reading recommendation. It was the same with the other kids, and the grandkids. She was Margaret Wilson, Mother of Readers. I said in a post this week, my father gave me sport, but my mother gave me words. It’s been difficult to find the right ones now. It’s unbelievable that she’s gone.

She’d even tolerate Macdonalds if it meant we’d read more books. In the eighties, she had a bribery deal going with us. If we went to Balwyn Library to choose new books, she’d allow us the fast food extravagance of a trip to the Maccas that shared the same carpark. One day, we were settling in for the rare treat of a junior burger, when out of nowhere she produced Tupperware containers. And what devilry was this?

They were filled with fresh lettuce, sliced tomatoes, cucumber, sliced cheese. ‘Mum, what are those!’ we hissed. ‘Well — ‘ she said, ‘I think my chopped salad is a fair bit healthier than their chopped salad. And I’ve got a nifty name for the burgers! We can call them Big Mags!

Big Mags. It’s mum’s Abbey Road in her discography of over-parenting.

There are some things I’ll always associate with Mum:

Stylish clothes

Fine art

Bead necklaces

A mastery of DIY dress ups

Half finished coffees

Cross word puzzles

Tuna mornay

Chops

Inadequate sunscreening

A VTAC insiders knowledge of which VCE subjects get standardised up and which go down;

Reedy hymn singing

3MBS and ABC Classic FM

Replacement swear words like ‘sheeba’, ‘ruddy’, and ‘blow me down’;

Apologetic phone calls, ‘I’m sorry are you at work?’;

Nervous gasps of ‘oh god’ from the passenger seat;

A love of bargains;

A desire for two for one surgery – go in for your hip replacement, get your varicose veins done at the same time! It brought untold joy when Harry had his lens columboma and herniated belly button fixed under the same anaesthetic;

Fine interior decorating and an obsession with things looking stylish. Let’s never forget that Mum made this tasteful grey lid cover for her recycling bin, because she thought the yellow lid was spoiling the ambience of her front yard;

Hairbrained schemes;

Scrabble;

Her hugs at the end of each visit;

The sense that when I was growing up, I had the best mum – the smartest mum, the most beautiful mum. And it went for dad too. The sense we had the best parents.

None of us were ready for this.

One of the sentences I love most in the eulogy section of Speakola is from Stephen Colbert, whose mother Lorna had eleven children, lost three, lived to 92, and was a supermum on par with our own. In the week of her death he said on his show:

I know it may sound greedy to want more days with a person who lived so long, but the fact that my mother was 92 does not diminish, it only magnifies the enormity of the room whose doors have quietly shut.

The fact is our own Mum’s room could have been so much smaller. I remember I was in the Clyde when I called her in 1993 and she told me that she had bowel cancer with lymphatic involvement. The pub was noisy and it was surreal — a 50-50 chance of survival, a coin toss. I remember feeling numb and sick. We had to face up to the possibility of losing her when she was just 48. Pippa said to me the other day, ‘I couldn’t have handled losing her then. We don’t get more time now, but imagine if we’d lost her then.’ The fact she did that year of chemo, and she did it so bravely and without a ‘why me’, or a word of complaint — and the fact we were lucky — so many people get cancer and just aren’t lucky.

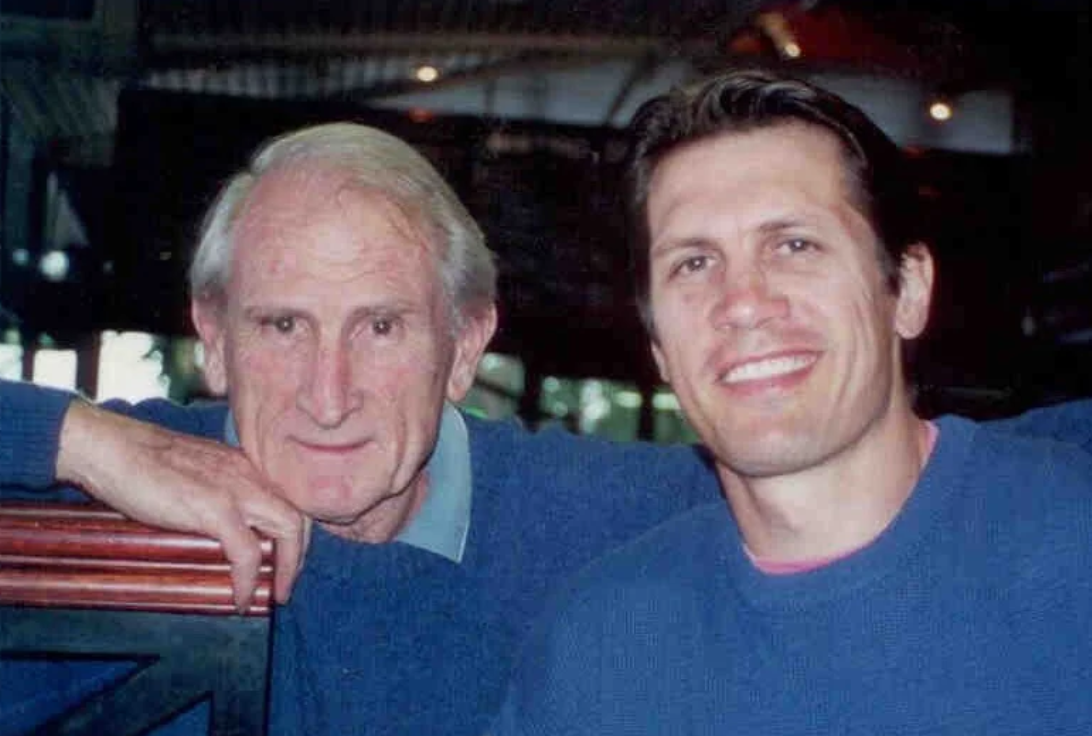

I’m so grateful my beautiful mum got to enjoy old age, got to meet her amazing, talented grandchildren, see then all get to double figures. I couldn’t have handled losing her then either.

I stood alone with Mum’s body on Tuesday and thanked her for everything. I thanked her for giving me life, and for giving me THIS life. She gave all of us her natural intelligence, which is part of the genetic pot luck, but she did everything else with such unbelievable energy and effort. She read to us, she put endless time into every interest or hobby, and she conquered the everyday mayhem of having four children, and Tam and I know, it’s a bloody mountain. Washing, bathing, shopping, medicating, comforting, disciplining, feeding, cleaning up, driving, counselling, in her case, a lot of optometry, just endless, thankless, mothering. Mum did it year after year, and she did it at A+ level.

Mum, I think of you at the end, alone, and it’s heartbreaking. I wish I’d been there to tell you I love you, to thank you for all that you’ve given us. I hope there wasn’t any pain, or if there was, that it was brief, I hope you weren’t too afraid, and that you felt our embrace — of Dad and us kids and your grandkids and your sisters and your friends. I really hope you felt that. We’re your boats that you set free upon the water. I know that you were proud of us. Your last words to me were on the phone at the airport were ‘have a great trip, you’ve earned it’. Well I’ll say the same back to you Mum. Have a great trip. You’ve earned it.

So long, Mum. We’ll miss you and think of you always.