26 February 2020, Melbourne Chevra Kadisha, St Kilda, Melbourne, Australia

Death is no stranger to my family; this is the third time in four years I’ve sat on that dreaded bench but today I’m alone with my mother and an empty space beside us. Back when the family plots were vacant, Johnny and I used to joke about who would be buried next to which parent. Which of us would get to listen to an eternal recitation of my mother’s poetic speeches about how being underground was not unlike her hiding spot in a black hole during the Holocaust, or who would be in direct earshot of my father’s jokes, his business commentary, and the TV tuned on full blast between ‘ or ‘Who Vonts to be a Millionaire?’ That was meant to be a long way off in the future. Today has put that discussion to rest; fate has determined it for us, with a twist no one could ever have predicted about the tragic order of things. Johnny and I also used to joke that we have great genes. Only last week one of my orphaned friends commented how unusual it is for our generation to have not one, but two living survivor parents. There’s also an irony in that, a painful one that has highlighted for our family the cruel randomness of life. Until Kerryn and then Johnny joined the inhabitants of this ghostly shtetl, my Dad came almost every Sunday for a consecration, before moving on to Chadstone to measure the condition of retail. While here, he would walk around the rows and aisles and point out the familiar graves, and with his Talmudic memory that could put a pin through the page of the life of any person, recite with precision an obscure or a hilarious story about Shloimeleh, or Moishe, or Meyer, or Freda, and the growing number of friends that were moving here until there was no one left back home to fill the four sides of a card table.

His memory and ability to connect the dots was one of his most remarkable features, and he carried it until his last day. You all know that look: his mind whirring like a poker machine until ding, he hits the jackpot and the details of your relatives pour out. ‘Ah. I knew your Zaida when he was a tailor in Flinders Street. I bought yarn off him for 2 pounds a yard in 1961.’ Or, ‘Ah, I remember your Buba danced with Chaim in Maison de Luxe on a Wednesday but he vos little and when his head bumped her tsiskes his vig fell off.’ And then his body would convulse with laughter until tears streamed out of his eyes, because he could actually see the scene unfolding before him in technicolour, every frame of it, going all the way back to Poland. No one has ever bumped into Yossl on the street without learning something they didn’t know about their ancestors. ‘Khai you,’ he would greet them, ‘Khu you,’ and then he’d tell you exactly Khu you were, rattling off stories like a Catskill comedian, a touch of the gossipy Yente in him, but never never was there a hint of malice and always always it was with loving humour. His humour. It was inbuilt in him and rippled through his whole body, his gesticulations, his passion, the way he lit up a room with his entire personality, and most of all with his eyes – sparkling, twinkling, blinking rapidly from over-excitement.

There’s the famous story from the Talmud of the House of Hillel and Shammai arguing through the night about whether God should create Adam and Eve. This argument was the one occasion the rival schools came to a unanimous agreement. No, they said, adding that now that the deed is done let’s deal with the consequences. In one sense they were right – my parents’ torments and suffering are testament to that, but on the other, if they could have gazed into the future and met my Dad, they would have reached a unanimous view the other way. Yossl wasn’t just larger than life; he created a parallel world of human possibility, of kindness, unconditional love, almost perfection. And like any world, his had its own language. Yosslisms, we called them. I’m sure you won’t hear a talk in the coming days that doesn’t refer to his unique vocabulary. The words weren’t random, they made grammatical sense. On their honeymoon when my mum was 19, they went to Sydney and she got appendicitis. Such a hard word for a migrant but he stripped away the medical pretensions and reduced it to its original source. A pain in the sitis. In his world, not everyone was Jewish, but as the title of the Yiddish album from the 1960s went, ‘When You’re in Love the Whole World Is Jewish’. ‘Is he or she Jewish?’ was always his first question, asked at the top of his voice, and it almost always pleased him to learn they were, except he feared, as he told me last week, an outbreak of antisemitism if either Sanders or Bloomingberg were elected. Otherwise, he would turn gentiles into Jews, such as Erin Brokovich, who he called Aron Berkovic, or the famous actor Maximilian Schell who somehow became his old friend, Muscatel.

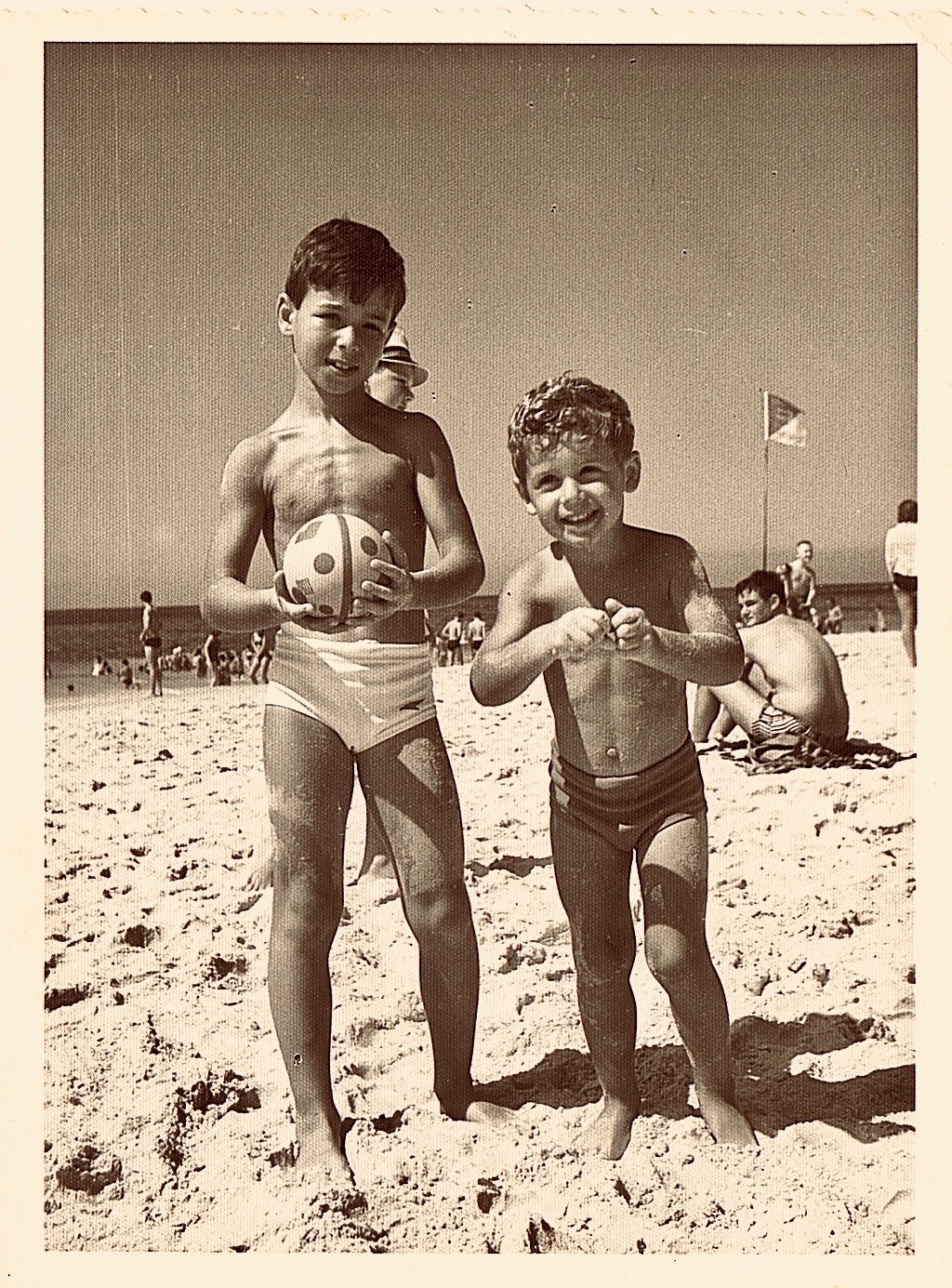

And then there was his most famous line. ‘Genia’s in Surfers and I’m in Paradise.’ This week that joke was tragically fulfilled, but until then, it was nothing more than a gag. For the truth is that my father never left my mother’s side for a second, he was her protector, redeemer and carer from the day he courted her as a new immigrant to Australia. ‘He spoiled me rotten,’ Mum will say, though she rightly takes credit that she tamed and anchored this handsome muscly man whose postwar image is captured in a series of photos of him on a motorbike, or sitting on the bonnet of his Humber Hawk, a cigarette dangling from his mouth.

And so it seems fitting, hard as it was for us, that his sudden and unexpected death took place in Surfers Paradise, because our times there carry so many threads from his life, and also of his death. I think of the holidays Johnny and I had as children at the Chevron with so many family friends, all of them survivors who never spoke of their past, but laughed around the pool or baked on the beach shmeared with baby oil with silver foil fans to attract extra sun, how they played red aces, and the times during my strict kosher days that my Mum furtively cooked kosher schnitzel for me in a bathroom from the patelnia (pan), while my father fanned the smoke away; until the high-rise apartments shadowed the beachfront and they made their home away from home in Allungah at Paradise Centre.

How did they do it, these survivors? Did they cast their trauma behind them on their boat to Australia, deliberately choosing life over death, or more likely, did they bottle it up inside them, the past and present entangled, shaping their personalities. Like the time when I sat with my Dad in their apartment in Surfers and I asked him to tell me his story, the only family tree he never wanted to explore, and I asked him how far the train was from the gas chambers when he arrived at Birkenau, and he casually pointed through the windows and said, ‘Oh, about from here to Cavill Avenue.’ Still, Surfers, it seemed, was a sanctuary they could escape to, but in more recent years, it was a different experience they were trying to escape, but could never shake off; the loss of Kerryn and then my brother and their son Johnny. At home, they were in deep grief within the four walls of their apartment which they would never leave. After a three year break, we were relieved that they agreed to resume their visits to Surfers. While it was easier to keep a vigilant eye on them in Melbourne, they were more independent, an elevator ride from the arcade and the restaurants and the Pokies. I won’t say they were happy, that would be expecting too much, but the pain was more bearable away from Melbourne where they felt caged in a prison of memories, eased through the daily phone calls from me and Anita which always began with a kvetch from my Dad about how hard life is because their grief always pursued them, even with the background tv sound of a tennis game and the roar of the expansive ocean.

My mum said we’ve been coming to Surfers for 62 years but nothing’s the same. The times when they knew everyone in every apartment of Paradise Centre, a community of Holocaust survivors, are gone. The people around them are unfamiliar, yet everywhere they go, they are celebrities. When Michelle and I were there last month, followed by visits from some grandchildren and other relatives, we were stunned. At Charlies, home to the famous scene when Dad asked for a breakfast of ‘risin toast’, and was served a bowl of ‘rice and toast’, the waiters loved them, learned his language and so understood that when Dad asked for Brigetta, he meant a bruschetta, or that rumash meant mushroom. In the newsagent where he ordered his weekly ‘Jewish News’ and pile of magazines for Mum which I took to the hospital, the woman knew him so well, and when the kids went to tell her yesterday what had happened, she rubbed her arms with goosebumps and eyes watering with tears. At the Italian restaurant on Orchard Avenue, the young owners embraced them both, and my Dad reminisced about how they played tennis together on the Ballah court 40 years ago, the court I stared at yesterday from the balcony where my mother was smoking her umpteenth cigarette, the court empty but imagining him with his distinct serve. In the Chinese restaurant on the Highway the owner almost fed his favourite customer with a spoon, and when we went to the casino, a French croupier who hadn’t seen my parents for ages greeted them excitedly, especially my Mum, with a cry of Georgina. We saw it at Hurricanes, overflowing with summer diners. ‘I’m sorry,’ I was told, ‘there’s a 90 minute wait.’ I despaired and we left but my Dad had hobbled off with his stick and within 30 seconds a young manager chased me and said, ‘we have a table for you.’

How did you do it Dad, this magic with people?

But what my parents missed more than anything during their times in Surfers, was their eight grandchildren - Timnah, Nadav, Mayan, Gilad, Karni, Gabe, Sarah, and Rachel and their partners and especially their great-grandchildren. They were their lifeline, every single one of them, who my father adored unconditionally and they in turn worshipped him. The day Gil and Shani brought the twins, Ziggy and Aya from Byron to visit them in Surfers, they were exploding with excitement and joy. Who knew that these two broken grief-stricken people could find the space to be so inflated with boundless love and life. And so it came as no surprise that the trigger for their planned return came this week after a 3 month stay. ‘Book us a flight for Friday,’ my Dad said. ‘Mummy’s ready. We want to be back for our Rudilu’s birthday on Sunday and his little sister Addy.’ That booking was never made. On Friday morning I got a call that my Dad had fallen. Everything that happened from this point personifies him. They were on Cavill Avenue and an ambulance was called. My Mum went up to the apartment to get his tablets and pack some things for him. He was in the ambulance when she returned, and the drivers said she has to leave. ‘No,’ she said, climbing in. ‘He would never leave me. Never.’ ‘I’m sorry, they said, you can’t come into the ambulance.’ ‘No,’ she repeated, ‘and if you want me to leave you will have to carry me out.’ They let her stay, of course.

I got a call from the hospital at 8 the following morning, 7 Surfers time. Twenty minutes later I was on my way to the airport, and when I arrived at the hospital, there was a bed made up for my mother who had slept by his side in his room. She explained they’d been in the emergency department till 4 in the morning. ‘How did they get my number at the hospital?’ I asked. ‘Dad remembered,’ she said, though he was delirious from a cocktail of drugs and from the pain in his fractured hip. ‘And why didn’t you ring me when it happened in the middle of the night?’ I asked, having only spoken to him about two hours before the fall. ‘Because Dad didn’t want to wake you and he told the hospital not to ring before 7 in the morning.’

From then on it was a barrage of meetings with doctors and filling out forms. Every encounter exposed a different angle of his life but nowhere did the truth come out more than when a nurse told me that he’d said when he arrived that he had come to Surfers for the funeral of his son. How true and revealing. As hard as they might try to compartmentalise their lives, the grief bleeds through the cracks, and expresses itself openly when the unconscious is given permission to speak.

From that moment, I became the mediator, stunned nonetheless that the two of them alone had got to this point with my Mum hard of hearing. ‘How old was he?’ they asked, handing me a form. I looked at the document and saw before me all the other documents I had uncovered from his youth. His birth certificate, his school records, his Auschwitz and Buchenwald registration, and immigration papers to Australia. Each one of them showed a different birthdate. In that second when the nurse waited for my answer, I thought of the schoolboy born in Wierzbnik-Starachowice in Poland, who jumped through the windows of Cheder to escape his teacher, and surpassed the naughtiest schoolboy act I’ve ever heard of by pissing in the pocket of the melamed’s coat; I thought of the boy being marched up a hill before he was barmitzvah with his brother Boruch from where he spent the next five years in a series of slave labour camps, before being sent to Auschwitz and then Buchenwald, where his father Leib had been killed in 1940, severed from his mother Hinde and sisters Marta and Yente who met their murderous fate in Treblinka. I thought of all the times someone whispered to him, tell them you’re older so that they sent you to a better section of the camp, or tell them you’re younger so you’re spared a certain death, or so you’re eligible for a visa to Australia. Time for my Dad didn’t move chronologically but was measured by a split-second decision that granted the possibility of extending his life.

So what do I tell the nurse and write in the form? His official date that he has lived by in Australia, 1 June 1929. Or is it more important for the doctors to know that he was born two years earlier, making him 92? Perhaps I should trick them and say what he believed, that he was born on April 11 1945, the day of his liberation, an age that matched his boyish personality. Or show them the photograph of him as an older man, pointing at the teenager in that iconic photograph of him a month after his liberation in Buchenwald. The message. Give him another chance to live.

His name. What do I write? Josek? Joe, as he was known in business? Or Yossl. Perhaps I should sing the Connie Francis song to him, as it was sung to him on his sixtieth birthday in our house at Aroona Rd, and as Rachel played it through her phone in his dying moments. One of his theme songs. ‘Ay yay yay Yossl, Yossl, Yossl, Yossl.’ It’s so sad, the kids said when they listened to it. I never thought of it as sad, until then.

And what of his surname. Baker. Born Bekiermaszyn. I’ve learned to spell it with its crashing Polish consonants. BEKIERMASZYN. One thing, the Nazis didn’t know how to spell it. Nor did the Jewish Agency, who listed him as a survivor on their registry in 1946, along with his brother Boruch. Together they went to Geneva with that name and spent the next three years being rehabilitated. I caught a glimpse of that transitional time once on a family holiday to St Moritz, when my Dad put on a pair of ice-skates, and whizzed around the rink. Who would have thought that I’d find myself living in that same place for four months last year with Michelle. I went in search of some of the gaps from his past, as though I could rewrite a section of The Fiftieth Gate. I found his name in the Swiss archives, and the location of the ORT Jewish training centre where he was sent after recuperating in a hospice from TB. ‘Do you remember where you lived?’ I asked him. ‘Oh, it was an orphanage,’ and he mumbled a name that no one in the Jewish community there recognised. ‘Could you see the fountain from where you lived?’ ‘Yes, I remember the shpritz,’ and eventually I found the approximate location of the Jewish welfare home in Switzerland. But what surprised me more than anything was that he asked the officials if he could use his stipend to live in a private home because – get ready for this – it was too noisy for him. My father, who had spent the previous five years in a string of death camps, summoned at dawn to the Appelplatz where he shouted out his number, had finally found sanctuary but thought it was too noisy. Perhaps, this was the beginning of his transition from the adolescent who endured filth and bedbugs, torture actually, deciding that he had expended all his energy on surviving and would later run at the sight of a moth, or a Mouse as he cried, leaving my Mum to do the swatting.

The documents in Australia show confusion about his name. Johnny’s birth certificate shows Bekiermaszyn, and it was soon after that he officially changed the family name to Baker, but upon receiving it, still signed it Bekiermaszyn. The name even carries on to my birth, back and forth. Perhaps he didn’t want to let go of the machine, because machines became his work life, starting with a single sewing-machine from which he built a business that exists to this day with his late and beloved brother Boruch and now the next generation on both sides led by Yechiel, Johnny’s place represented by Nadav, called Swiss Models appropriately after their time in Switzerland, though not really appropriately because it sounds like an escort agency.

And then there is his number. Instinctively, it was the one part of his body, punctured in hospital with a mess of needles, beeping machines and tubes, that we allowed ourselves to photograph. The nurses all noticed it and asked. I couldn’t resist telling them his story because perhaps, I hoped that the number would save him from death, as it did by sparing him from the gas chambers to the munition factories of the satellite camp, Buna Monowitz.

Before going in for hip surgery, I was told about the risks and had to sign forms. He emerged from surgery with a positive tone from the doctor. Soon after, things began to go wrong. His blood levels were dropping and eventually the doctors discovered internal bleeding. He would need another anaesthetic that same day to allow for a gastroscopy to locate and stop the bleeding. He was still delirious when I went in with my mother from the previous operation, but he still managed to get a few words out. His last words to us: Genia, hot gegessen? Have you eaten yet? he asked, looking at me and Mum. That was him, again, always thinking about others.

His situation improved and then we were told that he was critical and would die by the following day. As we sat by his bedside and watched the numbers on the monitors dive, the kids played music in his ear from their phone. ‘Zaida,’they said. ‘Listen.’ The first song was – what else? – ‘Rock Around the Clock’. That song is a beat that runs through his life, first danced alone when he came to Australia, about which he cheekily said that he went dancing 8 times a week, ‘tvice on Sunday’. Soon after my mother arrived, she caught his eye, and from that moment, they have rocked around the clock together, stepping in perfect harmony, and knowing each other’s movements like the inner mechanics of a Swiss watch. They danced it at Station Pier where their ship had docked in Australia for the launch of my book about them 25 years ago; they’ve danced it at every simcha, and at every Buchenwald Ball. And then, when tragedy began to strike our family, they led the dance at Gabe and Gabi’s engagement and wedding after Kerryn died. When Johnny was dying, I thought they would never be able to stand on their feet again, but when Gil and Shani got married soon after his death, they somehow rose from the grave they longed to share with him, and lifted all of our spirits, and especially Anita’s, by dancing. That’s it, I thought, the last dance. But their clock miraculously wound up again when Michelle and I married, and they mounted the stage by leading our family in their rapturous dance.

I still wanted more; we all did, even though my Dad was now using a stick to walk, and my Mum’s feet hurt. But the hands of the clock were ticking as the numbers on the ICU monitors plummeted. It’s been too many times that I’ve had to watch my mother say her goodbyes to the people she loved. My Dad found it harder to confront the deaths in our family, and would stand by the doorway, quivering and weeping. But my Mum, who has always been traumatised by the death of her mother at the end of the war, insisted on facing the inevitable. On Kerryn’s last day, she held her and shouted what would become the refrain of these past years, ‘Take me, If there’s a God in heaven then take me.’ And none of us will forget how she held Johnny’s hand, stroked his piano fingers as she called them, and pleaded to exchange places. ‘Why,’ she still beats her chest, ‘didn’t they take me instead of Johnny?’

And so on Sunday, she had to do it again, this time with her partner, lover, and carer of 67 years. She brushed his hair, and then made poetry out of every part of his body that she caressed. ‘These hands,’ she said, holding them, ‘worked so hard for our family.’ And then touching his chest, she said, ‘this heart, had only love for us.’ And then she turned to the nurses and begged them to hook her to the machines and take her with him. ‘How can I live without my Yossl, I don’t want to live, how can I?’ When one of us tried to console her by saying that she would be reunited with Johnny, she said, ‘What do you think I am? Stupid?’ We had to drag her out and I sat with my father and watched as his rate suddenly flattened to zero.

We played the songs to him, as I’ve said, but now without our Yossl, the song we will have to play is the one also sung by Connie Francis. It’s her other song, ‘My Yiddishe Mameh’ - my Mum who has literally walked in fier and vasser, crossed fire and water, for her children, Johnny and me. And in the day after while we waited in Surfers for my Dad to be taken home to Melbourne, my Mum, who has been begging for the heavens to open for her, showed strength. Between her cries of agony, she also chatted to us. She is blessed with gorgeous grandchildren who love her as they loved their Zaida, with great-grandchildren who no matter what make her smile, with a sister Sylvia who saw Yossl as a father and her kids Gid and Shelly, and she has always been blessed with daughters-in-law who have cared for her, Anita who has suffered so much and has loved and supported my parents since Johnny’s schooldays, Kerryn who was like a daughter to her after her own parents died, and Michelle who yesterday my mother asked to share with me. She made her instructions very clear about what she wants. I never would have imagined it but my Mum is now the head, the matriarch of the family. I feel so relieved to know that she still has a reserve of strength, though I know she will be more broken than ever.

There has always been a song my father would sing first for his two sons, then for each of his grandchildren, and now for his great-grandchildren. Life has a strange way of bringing beginnings and ends together. It’s now for us to sing it to him, our baby, our redeemer, our hero.

Shlof shoyn mir my, Yosseleh, mayn sheynshik

Di eygelekh, di shvartsinke, makh tsu,

A yingele vos hot shoyn ale tseyndelekh (!)

Muz nokh di Tate zingen, Ay Li Lu.

Lu Lu.