5 February 2015, Melbourne Cricket Ground, Melbourne

I’d like to begin by sharing with you the opening of the memoir that Harry intended to write, but never progressed beyond the words I am about to read. It was tentatively titled The Boxer’s Son and this is how it began:

“When my father’s heart stopped beating, I was nursing his hand, stroking the back of it. His right hand, lumpy and gnarled: a paw that always seemed a bit large for such a small and compact man. It had been broken more than once, and never well mended, and the bumps around the back of the thumb made it feel like a chunk of mallee root.

“My father had been a prize-fighter, a bantamweight professional boxer, and that mis-shapen right hand had been his most significant tool of trade. It had done most of the damage he inflicted through close to 150 fights, many of them 20-rounders. It had even killed a man, another boxer who happened to be his best friend.

“I was perhaps 10 years old, maybe 12, when I first learned about the death of George Mendes. It was there in his scrapbook….”

And that is as far as he got.

*******

I grew up with the story of how Harry’s dad, my grandfather who we all called Pa, killed George Mendes, his best mate, after a reluctant Pa agreed to the fight because Mendes was having a child and needed the money; how Pa tragically caught him while he was mid-air, switching feet, with the result that he hit his head hard on the canvas and died; and how that fight effectively ended two brilliant careers.

What I didn’t know, until the last week, was how Pa got into the fight game. The answer was in one of dad’s scrap books.

As a paperboy, Pa fought for the prime spot to sell papers at Flinders Street station, though he had never been taught how to box or even been in a gym. One of the fight promoters of the time, Arty Powell, used to allow a few of the paper boys in to see fights for free at the Pavillion, opposite Her Majesty’s Theatre in Exhibition Street, on condition that, in the event that someone on the bill failed to front up, they would enter the ring.

On March 25, 1917, it happened and young Harry, 15 years old and weighing seven stone and nine pounds (or 48 kilos), stepped into to the breach. He knocked out his opponent in the first round, and his next two fights ended the same way. Pa’s real name was Arthur Gordon Parish, but the promoter called him Harry Gordon and it stuck.

Pa went on to become one of the gamest fighters Australia ever produced, and he taught his son how to box in the back yard of their home in Elwood, with the result that Harry became middle weight champion at Melbourne High.

*****

If there was another trait that Harry inherited from his father, it was humility, and the ability to mix easily in any company.

Inside the Elwood house, on the lino kitchen floor, Harry’s mum, a former singer and dancer, with a capacity for exaggeration, used to teach little girls how to tap-dance to make some extra money during the Depression. So Harry learnt to tap-dance, too. Whatever imagination and creativity he possessed, Harry has said, came form his mum.

*******

Two weeks ago, I nursed my father’s hand, along with Johnny and Sally, and Joy, when his big heart stopped beating. It was in better shape than Pa’s.

In the preceding days, as we sat with Harry, I read to him from Hack Attack, Nick Davies’ account of how he broke the hacking scandal in the British press. It’s a pacy tale, and Harry enjoyed listening to it and would nod approvingly when Davies turned a neat phrase.

Early on, Davies observes that reporters are really very similar, and tend to run on a volatile combination of imagination and anxiety and luck. As generalisations go, it’s a good one, but it didn’t apply to Harry, who never seemed anxious and was propelled by a mix of curiosity, creativity, idealism and an ability to see some things that others could not.

Others in the press box who watched John Landy pass up the chance for a world record, to see that a fallen mate was OK, knew they had witnessed something special, but only Harry called it for what it was: one of the finest acts in the history of sport.

*****

In Hack Attack, Davies also paints a rather frightening portrait of the newsrooms of Fleet Street, especially the tabloids, suggesting they are run by puffed-up, foul-mouthed, self-important editors who can’t tell the difference between leadership and spite.

What struck me was how different this culture was from the one Harry nurtured when he was editor at The Sun and, later, editor-in-chief at the Courier Mail in Brisbane. Harry’s management strategy was to help his colleagues be the best they could be by encouraging, not intimidating, by rewarding (if only with his time and advice), not punishing.

The number of journalists who have made contact in recent days to describe how Harry either hired them, inspired them or shaped their careers is in the dozens, and reads like a who’s who of the profession.

It reminds me of the number of coaches who learnt their craft under Yabby Jeans at Hawthorn in the 80s, or the still growing band of Alastair Clarkson protégés who are making their marks at other clubs.

*******

Harry was blessed to have two innings in journalism and love. The first career began as a 16-year-old copy boy on the Daily Telegraph and Harry was, to quote from the title of his first book, a young man in a hurry: at 21, he was in Singapore, covering the execution of Japanese war criminals; at 24, in Korea covering a brutal war and seeing active service; at 27, in Helsinki, covering his first Olympics; and rising from one of the more junior to the most senior position at the Herald and Weekly Times during a career spanning 37 years.

He ran The Sun in the late sixties and summed up his feelings as editor in a note I found in his computer: “Finger on the pulse,” he wrote. “Answered every letter, loved it, great staff, great papers, big stories: the Kennedys, the moon landing, West Gate Bridge disaster, Ronald Ryan… great circulations. A golden time.”

*****

His first love was my mum, Dorothy Scott, who a was a member of the Maroubra Surf Life Saving Club.

Mum’s passing in 1984 was the great tragedy of Harry’s life, and his departure from the Herald and Weekly Times soon followed. It was then that the generosity he had shown to others was reciprocated with offers to be a contributing editor to the new Australian edition of Time magazine; to return to the Olympics and write columns at Seoul; to write The Hard Way, the history of the Hawthorn Football Club, which I worked with Harry to update as One For All in 2009; and to become the official historian of the Australian Olympic Committee.

The second love was Joy, who lived over the side fence and would toss over eggs or bread when Harry’s fridge was bare.

*******

Harry achieved a lot, but he had a lot of fun along the way, getting as big a kick out of frivolous things as he did standing up the Victorian Parliament, or Joh Bjekle-Petersen. Lou Richards tells the story of the day they sat at our house at Hawthorn, writing captions for the backs of footy cards and laughing themselves silly at their own jokes.

He loved his pattern of life, from the hall of fame selection committee meetings; to the trips away with Joy; to family get-togethers at Christmas; to Grand Final week, starting with the Carbine Club lunch, building to the lunch with old colleagues in journalism on the Friday and culminating with the big game.

This year he saw his 12th Hawthorn premiership, and after watching the game we met my kids and their mates at the Blazer Bar for a few celebratory beers. One of them, a Hawthorn supporter, later told me that talking with Harry was the highlight of his grand final.

*****

What sort of father was he? Most of all, he was passionate, someone who greeted each day with enthusiasm and a sense of adventure, generosity and optimism – traits that never left him. He was also competitive, whether the game was 21-up basketball, or beach cricket or (when he was younger) kick-to-kick.

He was proud of his kids and loyal, too, and sometimes to a point that defied logic. At my wedding, for instance, my brother had a disagreement with the person who ran the restaurant where we were celebrating and, as he tends to do, employed some colourful language to make a point. When the owner complained to Harry, he replied that it could not have been John because “my boys don’t swear”!

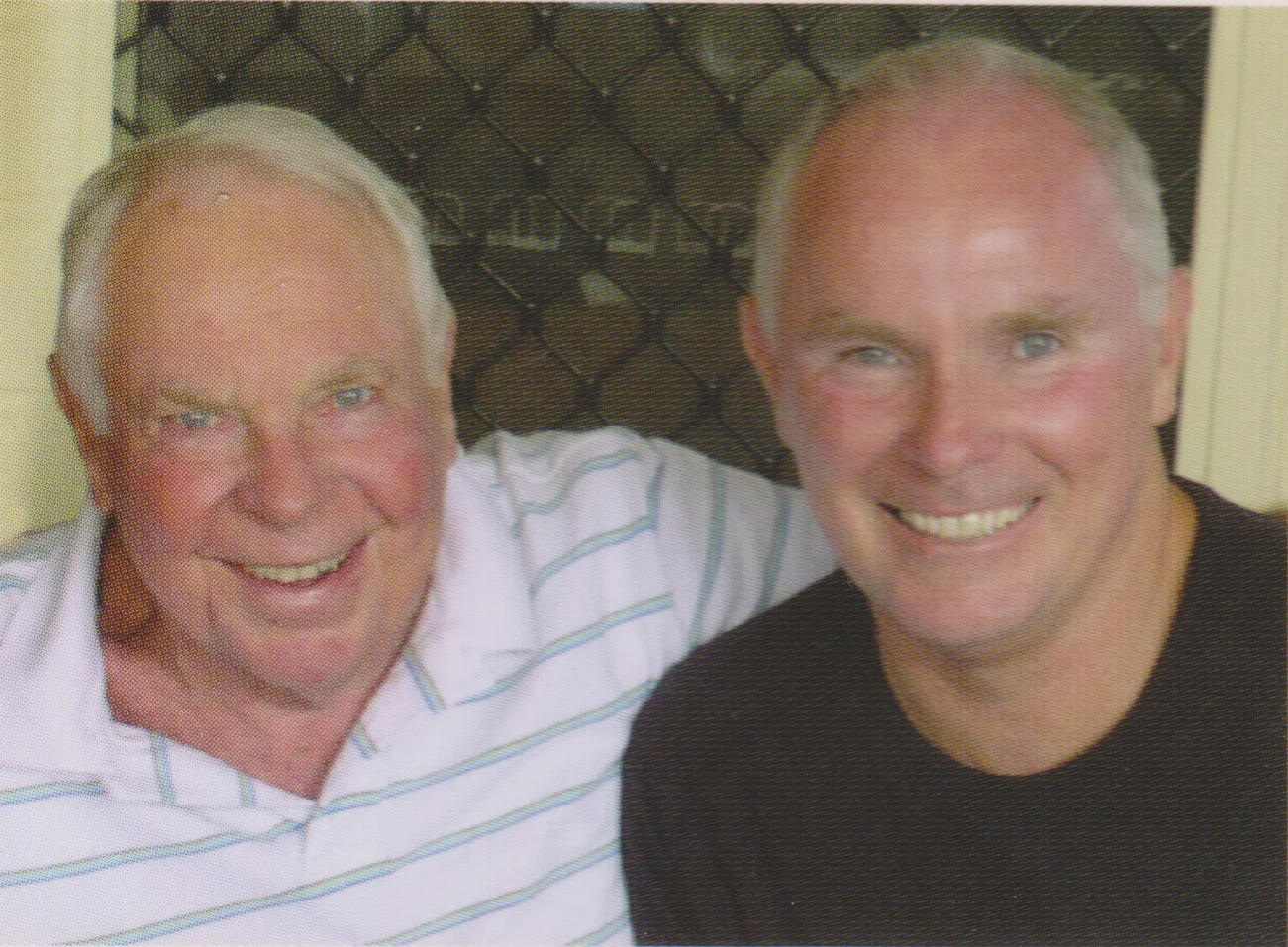

Over the years, Harry became more a sibling than a parent to us kids and even our kids, and Johnny, Harry and I were the Gordon brothers. We called each other 'kid' and I will always fondly recall how, when he came back from one extended trip overseas, he said: “I miss you calling me 'kid', kid.”

In hospital the day he died, I told him how I’d miss reading him the first paragraph of bigger pieces I had written before they were published. From underneath the oxygen mask, he retorted: “And the last!”

Harry worked hard on his first and final paragraphs, and what came in between flowed like a river. His last words were among his finest.

Addressing the family he told us he’d enjoyed a wonderful life and how grateful and full of love he felt – a sentiment that would be magnified if he was in this room today.