23 October 2008, University of Sydney, Australia

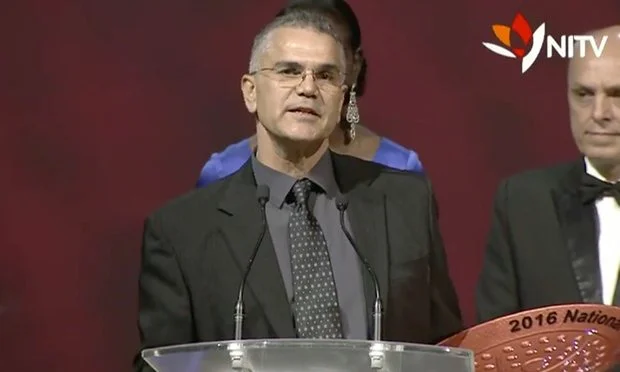

Tom Calma s a Kungarakan elder and Iwaidja man from the Northern Territory who delivered this during his tenure as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner at theAustralian Human Rights Commission

I acknowledge the traditional owners of the land where we are meeting tonight, the Gadigal peoples of the Eora nation. I pay my respects to your elders and to those who have come before us. And thank you to Chicka Madden for your generous welcome to country. Chicka and I spent a term together on the Board of Aboriginal Hostels.

Can I also acknowledge the Perkins family (Eileen, Hetti, Rachel and Adam), and thank Sydney University and the Koori Centre for the great honour and privilege of being invited to address you this evening in memory of a truly great Aboriginal leader and great Australian.

Can I also pay my respects to all of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students who will graduate tonight. I am also honoured to share this stage with you as we recognise your achievements.

There can be no more fitting legacy for Dr Perkins than to see – every year – an increasing number of our Indigenous brothers and sisters graduate from this esteemed university. We have certainly come a long way from 1965, when Charles Perkins was the lone Aboriginal student graduation ceremony. Thankfully, the graduation of Aboriginal men and women is not such a rarity these days – although I would still like to see a lot more of you!

Some reflections:

We have gathered in this Great Hall tonight to honour and remember Charles Perkins, a man who had the courage to bring Australians together in a quest for equality.

As I considered what I might say about Charlie tonight, it immediately became clear to me that no few well chosen words could sum up his life and his legacy.

Charlie was a proud Arrente man, a scholar, an avid sports fan and footballer, a bureaucrat, an agitator, and a human rights champion.

And if we look back at each of the major developments in Indigenous policy since the 1960s – Charlie was always there. Sometimes he was an outsider breaking down walls and fighting for justice for Aboriginal people. And other times he worked from within the system – but with much the same approach, and almost always with some results.

Be it the freedom ride and the fight for people’s rights to swim at the local pool or to go the movies without being cordoned off like second class citizens – right through to the 1967 Referendum, the land rights movement, the building of major institutions such as the Aboriginal Development Commission, the NAC, ATSIC and the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation – Charlie was there, and always had plenty to say.

If there was injustice – he didn’t shy away from it, even if the issue was controversial, or difficult for the majority of Australians to face up to.

In the 2007 documentary ‘Vote Yes for Aborigines’, Warren Mundine remembered the Charles Perkins of 1967 as an immaculately groomed campaigner – polite, well spoken, dressed in a suit with a thin tie, and ‘the shiniest black shoes you’ve ever seen’.

Yet many people would also clearly remember the anger and passion that Charles brought to so much of his dealings with government throughout his life – from the early years on the freedom ride campaign, to being suspended from his role as a senior public servant for calling the actions of a state government racist, to furiously yelling at John Howard about his refusal to acknowledge the existence of, and apologise to, the Stolen Generations at the Opera House shortly before his passing in the year 2000.

There is no shortage of public achievements by which we can remember Charles Perkins.

But to relegate Charlie’s achievements to these memories would fail to capture another important part of his legacy. For Charles was also a role model to all of us, as well as a son, a husband, a father, and a grandfather.

And I think that everyone that has involvement with the Perkins family will know that they all embody Charlie’s strength of character and determination. Over the past few weeks, I’m sure that many of you will have been watching Charlie’s daughter Rachel’s excellent series “The First Australians” - and will agree that the Perkins family continues, today, to contribute powerfully to efforts to change the way that mainstream Australia thinks about the Indigenous peoples of this nation.

Charlie had a tireless dedication to human rights and social justice for Indigenous Australians. And I speak to these issues tonight in his memory.

How far have we come?

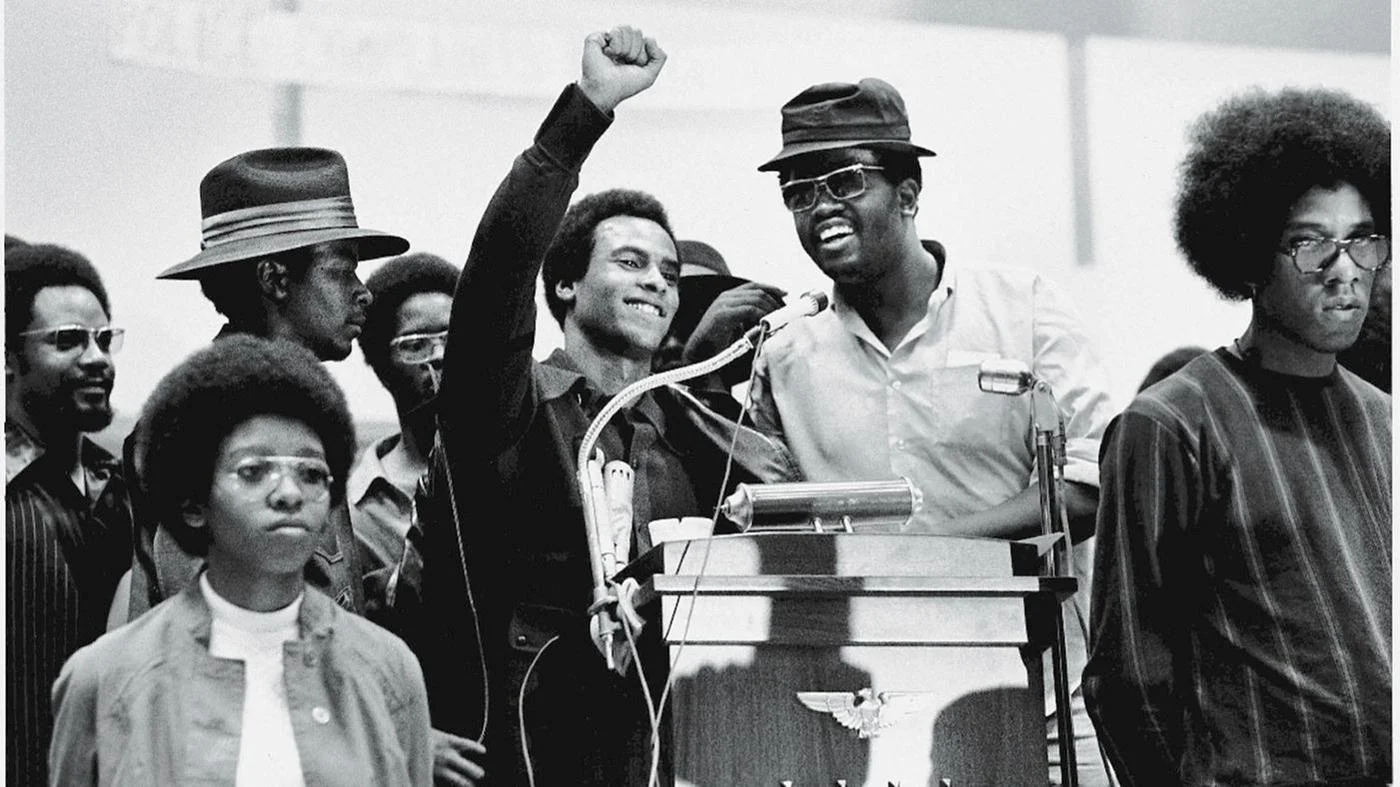

In the introduction to Charlie’s autobiography ‘A Bastard Like Me’, Ted Noffs argued that ‘it is not too much to say that Charles Perkins is to the Aboriginal population in Australia what Martin Luther King Jr was to black people in the United States’.

And like King, at all times, Perkins’ vision was one of equality of rights, equality of access, and freedom from discrimination.

But perhaps more than ever, at this time in history, the comparison of King to Perkins is a telling one.

In just two weeks, we may well see the first black candidate elected to the presidency of the United States of America. Today, in the United States, King’s dream - that one day a man might be judged not by the colour of his skin, but by the content of his character, seems one step closer to realisation.

But when we look closer to home, and reflect on our own progress in Australia, we see a markedly different picture.

As was the case in America, powerful calls for equal rights were heard in Australia in the 1960s. But despite the gains that we have made, we have hardly any formal human rights protection mechanisms at all.

What I want to do in my remarks tonight, is indicate to you that the gaps in our legal system around human rights protection have a real effect on the opportunities and life chances that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have in Australia today.

In my view, one of the most perverse developments over the past decade has been the bad press that human rights have consistently received in public debate within Australia.

And according to some, it is time to ‘get serious’ and face up to ‘practical issues’ facing Indigenous peoples like ‘addressing disadvantage’ rather than concerning ourselves with issues such as human rights for Indigenous peoples - which after all, are really only symbolic.

But let me put this question to you: is our democracy really working so well for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the year 2008?

Unlike all other western democracies, in Australia we have no Charter of Rights – not for Aboriginal people, and not for anyone! And as the Northern Territory intervention demonstrates, the commitments that we do have across our society to non-discrimination and to equal treatment for Indigenous peoples are such that many in our society deem it acceptable to simply ‘switch off’ the protection from racial discrimination when it is expedient to do so.

Unlike Canada, we have no constitutional recognition of the rights and status of our First Nations peoples. In fact, we are distinguished, (and I use that word advisedly!) as perhaps the only country which has a Constitution that permits discrimination against its indigenous peoples on the basis of our race.

Unlike New Zealand, we still have no treaty, or permanent mechanism for the ongoing resolution of land claims through a process of self-determination.

And unlike the vast majority of member states of the United Nations, we have not yet endorsed the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Now, if human rights were only symbolic, maybe none of these things would matter very much. If things were fine just the way they were, and we had a system of government where we were well represented, well serviced, and well protected, then maybe we could forget conversations about human rights for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

But let’s look at the reality.

Today in Australia, we see a federal parliament which has no Indigenous members.

We see a system of service delivery to Indigenous peoples – by governments at both the federal and state levels – that struggles to deliver the most basic of services for the benefit of Indigenous peoples.

We see a system with too many bureaucrats who do not see themselves as accountable to Indigenous peoples or as having responsibilities to ensure that Indigenous peoples benefit from their efforts.

We see a system in which the likelihood of an Indigenous person rising to the top of the bureaucracy – like Charlie and his niece Pat Turner did – is unlikely to occur anytime soon - except for a very small number of senior Indigenous bureaucrats in our federal and state governments.

And we see limited engagement with Indigenous peoples in the setting of policy and programs, with no formal mechanism for Indigenous national representation at present, or a formal commitment to self-determination.

I suspect Charlie would have had a lot to say about what we’ve got in 2008.

But it should be clear to all of us tonight, even without Charlie with us, that we should not be content simply resting on our laurels, and celebrating the gains that we have won.

Tonight, I will argue that there remains a pressing need to question inequality in Australian society, and to question how we protect the most vulnerable among us. And that is why I have titled this oration, ‘Still riding for freedom: An Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Human Rights Agenda for the Twenty-First Century’.

I see the next few years as critical in our continued struggle for equality and the recognition of the rights of Indigenous peoples.

There are a few reasons for this.

First, we are at a time of rapid advance in the recognition of Indigenous peoples rights at the international level. The passage of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples has provided much momentum throughout the UN system to strive to improve how Indigenous peoples’ rights are protected. We can expect that over time this increased focus will place greater expectations and scrutiny on our approach here in Australia – be this through reporting to human rights treaty committees, the universal periodic review processes of the UN Human Rights Council or through changes to global practices for development cooperation.

And second, we have the prospect of renewal with a new federal government that has signalled its intention to enter into genuine partnerships with Indigenous peoples. This has been a central feature of commitments made to Close the Gap in Indigenous health inequality and was very strongly articulated by the Prime Minister in his Apology speech back in February this year.

Of course, the actions are still needed to match the rhetoric of the new government.

So tonight, I want to consider the following main elements of a human rights agenda for Indigenous peoples in Australia:

- Changing how we conceive of poverty so it is treated as a human rights issue;

- Addressing the lack of formal legal protection of human rights in our legal system; and

- Providing due recognition to the First Nations status of Indigenous Australians.

Conceptualising poverty as a human right

As the starting point, let me start with a deceptively complex issue that I see as one of the most profound challenges that we face in Australia today. This is the challenge of redefining how we conceive of poverty so it is squarely addressed as a human rights challenge.

For too long now, we have heard it argued that a focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples rights takes away from a focus on addressing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples disadvantage.

This approach, is in my view, seriously flawed for a number of reasons. It represents a false dichotomy - as if poorer standards of health, lack of access to housing, lower attainment in education and higher unemployment are not human rights issues or somehow they don’t relate to the cultural circumstances of Indigenous peoples.

And it also makes it too easy to disguise any causal relationship between the actions of government and any outcomes, and therefore limits the accountability and responsibilities of government.

In contrast, human rights give Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples a means for expressing their legitimate claims to equal goods, services, and most importantly, the protections of the law – and a standard that government is required to measure up to.

The focus on ‘practical measures’ was exemplified by the emphasis the previous federal government placed on the ‘record levels of expenditure’ annually on Indigenous issues.

As I have previously asked, since when did the size of the input become more important than the intended outcomes? The Howard government never explained what the point of the record expenditure argument was – or what achievements were made.

Bland commitments to practical reconciliation have hidden the human tragedy of families divided by unacceptably high rates of imprisonment, and of too many children dying in circumstances that don’t exist for the rest of the Australian community.

And the fact is that there has been no simple way of being able to decide whether the progress made through ‘record expenditure’ has been ‘good enough’. So the ‘practical’ approach to these issues has lacked any accountability whatsoever.

It has also dampened any expectation that things should improve from among the broader community. And so we have accepted as inevitable horror statistics of premature death, under-achievement and destroyed lives.

I am sure history will show that this past decade was one of significant under-achievement in addressing Indigenous disadvantage – and quite inexplicably, under-achievement at a time of unrivalled prosperity for our nation.

If we look back over the past five years in particular, since the demise of ATSIC, we can also see that a ‘practical’ approach to issues has allowed governments to devise a whole series of policies and programs without engaging with Indigenous peoples in any serious manner. I have previously described this as the ‘fundamental flaw’ of the federal government’s efforts over the past five years. That is, government policy that is applied to Indigenous peoples as passive recipients.

Our challenge now is to redefine and understand these issues as human rights issues.

We face a major challenge in ‘skilling up’ government and the bureaucracy so that they are capable of utilising human rights as a tool for best practice policy development and as an accountability mechanism.

We have started to see some change with the Close the Gap process. As you may know, the Rudd government, and all Australian Governments through COAG, have agreed to a series of targets to be achieved over the next five to ten years to start the process to close the gap in health status and ultimately in life expectancy, as well as across a range of other measures.

In March this year, the Prime Minister, the Leader of the Opposition, Ministers for Health and Indigenous Affairs, every major Indigenous and non-Indigenous peak health body and others signed a Statement of Intent to close the gap in health inequality which set out how this commitment would be met. It commits all of these organisations and government, among other things, to:

- develop a long-term plan of action, that is targeted to need, evidence-based and capable of addressing the existing inequities in health services, in order to achieve equality of health status and life expectancy between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non- Indigenous Australians by 2030.

- ensure the full participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their representative bodies in all aspects of addressing their health needs.

- work collectively to systematically address the social determinants that impact on achieving health equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

- respect and promote the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and

- measure, monitor, and report on our joint efforts, in accordance with benchmarks and targets, to ensure that we are progressively realising our shared ambitions.

These commitments were made in relation to Indigenous health issues but they form a template for the type of approach that is needed across all areas of poverty, marginalisation and disadvantage experienced by Indigenous peoples.

They provide the basis for the cultural shift necessary in how we conceptualise human rights in this country. Issues of entrenched and ongoing poverty and marginalisation of Indigenous peoples are human rights challenges. And we need to lift our expectations of what needs to be done to address these issues and of what constitutes sufficient progress to address these issues in the shortest possible timeframe so that we can realise a vision of an equal society.

This will be deceptively hard to achieve and it will take a generation. But it is a vital part of the human rights challenge for all Australians.

Addressing the lack of formal legal protection of human rights in our legal system

A different but no less formidable or important challenge is addressing the lack of formal protection of human rights in our legal system.

There are two main challenges here – first, is the lack of protection provided for many basic human rights; and the second, is the vulnerability of the protection that does exist.

Many people are surprised when they learn that we have endorsed and supported human rights standards for over forty years in the international arena, and yet have failed to give practical meaning and protection to many of them in our domestic legal system.

This isn’t simply a failure that sits at the international level. It is a failure to deliver on commitments to the Australian public about the basic standards of treatment that they can expect at all times.

We have parked most human rights at the door, leaving Australian citizens in the unenviable position that in relation to the majority of rights, we don’t have any formal mechanisms for considering how laws and policies impact on people’s rights or for providing redress where rights are abused.

As an example, we have very limited enshrinement in our legal system of the rights contained in the two main international human rights treaties, on economic, social and cultural rights and civil and political rights.

This is an issue that ultimately affects all Australians. Although usually, the consequences of such a lack of protection impacts the most on those who are the most vulnerable and marginalised in our society – such as Indigenous peoples.

The end result is a legal system that offers minimal protection to human rights and a system of government that treats human rights as marginal to the day to day challenges that we face.

We need better protection of human rights in our legal system as well as mechanisms to ensure that the courts, the executive and the Cabinet have human rights at the forefront of their thinking at all times.

Accordingly, I strongly endorse the calls for a Charter of Rights that can provide comprehensive recognition of human rights consistent with our international obligations as well as remedies where rights have been abused.

I see another equally important role for a Charter in our society.

A Charter of Rights can play a vital role in improving the accountability of government by requiring a greater focus and concentration on identifying the human rights implications of policies and legislation when they are formulated. This is through mechanisms such as statements of compatibility and human rights analyses of proposed new laws.

By putting human rights issues front and centre and making bureaucrats and politicians explicitly consider what the human rights impacts of their laws and policies are, a Charter of Rights can have a transformative effect in improving the decision making process. It would also hopefully prevent many human rights violations from occurring in the first place.

We have lacked appropriate coverage and protection of human rights for too long, and a Charter of Rights is long overdue. This will be a key issue for debate in the coming year and so I hope that we will finally take this important step and close the ‘protection gap’ that currently exists for all Australians.

But there is a second aspect to our current system of legal protection that also needs to be addressed. This is an issue that has very acutely impacted on Indigenous Australians.

That is the vulnerability of the human rights protections that do exist in our legal system.

On three occasions in the past twelve years we have seen racial discrimination protections removed solely for Aboriginal people by the federal government. This has been in relation to the exemption from heritage protection laws of the Hindmarsh Island bridge in South Australia; the Wik ten point plan amendments to the Native Title Act – provisions that remain in breach of our international treaty obligations I might add – and the exemption from the Racial Discrimination Act of the NT intervention legislation.

Our existing system works like this.

States and territories are bound by the protections of the Racial Discrimination Act (or RDA) by virtue of the Australian Constitution. This provides that state and territory laws will be invalid to the extent that they are inconsistent with a valid law of the federal Parliament – such as the RDA.

In both the Hindmarsh Island and Wik situations, the federal Parliament authorised state and territory governments to introduce discriminatory laws against Indigenous peoples. Because this was authorised by a federal law that was more recent than the RDA, the more recent law prevailed and the discrimination was legally valid. The fact that it was legally valid does not change the fact that it is in breach of our international obligations so you then also have an inconsistency between our domestic legal system and international obligations.

Notably, if the state or territory levels of government initiated such discriminatory provisions themselves then they would be found to be constitutionally invalid – as happened in Queensland in 1985 when they sought to prevent Eddie Mabo from pursuing his claims of native title by acquiring all native title rights for the Crown, and in Western Australia in 1995 when the WA government similarly sought to extinguish all native title rights across the state and replace it with a lesser right. So the states and territories cannot initiate racially discriminatory actions themselves.

The Wik ten point plan amendments also involved the Commonwealth discriminating against Indigenous peoples themselves – not just through the states and territories. As the RDA is an ordinary enactment of the federal parliament the principle of parliamentary sovereignty applies to it – meaning that laws that are made at a later time will override the RDA to the extent of any inconsistency.

So the states and territories must comply with the RDA, unless the federal Parliament exempts them. But the federal Parliament is not so bound and may legally discriminate against Indigenous peoples if it so chooses - so long as it does so through the passage of a law that the Parliament has the constitutional power to enact in the first place.

And this is where some of you may also be very surprised. For our Constitution permits the federal Parliament to enact laws that racially discriminate against Indigenous peoples – and indeed against any other group based on race.

This is how. Section 51(26) of the Constitution – the very provision that Charlie and others fought so hard to amend through the 1967 Referendum – enables the federal Parliament to make special laws for the peoples of a particular race. This has been interpreted by the High Court as meaning any special laws – including ones that are discriminatory. Surely this is a perversion of the intention of the 1967 referendum.

We need to revise the scope of Section 51(26) of the Constitution – the so-called ‘races power’ so that we clarify that it only permits the making of laws that are for the benefit of people of a particular race. There is no place in modern day Australia for legalised discrimination.

But I also see a need for constitutional reform to go further than this.

For example we could consider inserting into the Constitution a new provision that unequivocally provides for equality before the law and non-discrimination. Article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights provides a starting point for what such protection might say. It reads:

All persons are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to the equal protection of the law. In this respect, the law shall prohibit any discrimination and guarantee to all persons equal and effective protection against discrimination on any ground such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.

It is arguable that this protection would have addressed the serious deficiencies of the NT intervention upfront and ensured that actions were more fairly and better targeted from the outset.

I would also support a new preamble for the Constitution that recognises Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples within the fabric of the nation. However, I must say that the preamble is secondary to the above issues and should not be used as an alternative to efforts to ensure that one day we have a Constitution that does not permit racial discrimination.

So a major challenge that we face is how we ensure that our commitment to non-discrimination and equality, and to human rights more generally, is not something that is swept aside whenever it gets difficult or inconvenient or when it is expedient to simply override this protection.

And on that note, let me comment briefly on the NT intervention.

I have been a strong critic of aspects of the intervention – particularly the way that it has resorted to racially discriminatory measures to achieve its purposes. This is something that I have said from day one will undermine all the positive efforts being undertaken. I also firmly believe that measures to protect children can and should be undertaken, but that they can be achieved without discrimination.

I think that the Review Team on the intervention was spot on in identifying the fundamental flaw of the intervention when they state in their report that:

There is intense hurt and anger at being isolated on the basis of race and subjected to collective measures that would never be applied to other Australians. The Intervention was received with a sense of betrayal and disbelief. Resistance to its imposition undercut the potential effectiveness of its substantive measures.

Measures that deny people basic dignity will never work. As the NT Review report notes, it is this singular problem that has undermined the effectiveness of the intervention and has broken down the trust and relationship between government and Indigenous peoples across the Territory.

Now I was very interested to read the editorial in The Australian this past weekend. It read:

You would have to search hard in today's Australia to find anyone who does not support the broad principles of equality before the law or who does not abhor racial discrimination...

At the time (the intervention was introduced), The Weekend Australian supported the suspension on the grounds that the rights of Aboriginal children to a decent life free of fear trumped every other consideration...

It is now clear, however, that the (Racial Discrimination) act can be safely reinstated without hindering the intervention. The reinstatement of the act deserves bipartisan support.

My Social Justice Report 2007 provides a ten point plan on how to achieve this. That plan also shows how the Minister for Indigenous Affairs could today remove a significant portion of the discriminatory provisions of the intervention legislation through using her existing administrative powers – without recourse to Parliament.

The Rudd government must act decisively on this issue to ensure that the intervention legislation is consistent with human rights and is non-discriminatory. A failure to do so will fundamentally contradict the commitments that the government has made – including those to Close to Gap and to work in genuine partnership with Indigenous communities.

But there are two comments by The Australian that I think illustrate this deeper problem of human rights protection in Australia that I have been discussing.

The first is the suggestion that you can ‘turn on’ and ‘turn off’ protection against racial discrimination whenever it suits. And the second is that the only way children could be protected in the NT when the intervention was introduced was by racially discriminating against them and against their families and communities.

I am deeply troubled by the suggestion that there may be circumstances where protections against racial discrimination can be removed for some ‘greater good’. It raises the unsettling question of who decides what the greater good is? Misplaced best intentions have been something Indigenous peoples have suffered for a long time in this country.

I also reject totally the suggestion that resort to discrimination was necessary in order to protect children. I also totally reject any suggestion that at the time of the intervention we faced a crossroads of choosing between either racially discriminating or protecting women and children. This was a choice that was set up by design and it was, and still is, avoidable. The only sound policy choice is one where children are protected and are not discriminated against as well.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child itself is explicit in Article 2 that discriminatory measures can never be justified on the basis that they further other human rights and that there needs to be a consistent approach in how all human rights are applied.

Nevertheless, the recommendations of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) Review Report now provide an opportunity to refocus the Federal Government’s efforts from an emergency to community development approach in improving the lives of Northern Territory Aboriginal children.

There is a major challenge for communities across the Northern Territory, and Australia, to demonstrate that they understand and accept that women and children have rights to be safe and free from violence. And there are many examples that show that this is in fact the view of Indigenous people in the NT.

For example, in July there was a major men’s health summit on the lands of Charlie’s people – the Arrente – which provided clear leadership from Indigenous men about addressing violence and abuse. The outcomes of that Summit are contained in the Inteyerrkwe Statement. It reads:

We the Aboriginal males... gathered... to develop strategies to ensure our future roles as grandfathers, fathers, uncles, nephews, brothers, grandsons, and sons in caring for our children in a safe family environment that will lead to a happier, longer life that reflects opportunities experienced by the wider community.

We acknowledge and say sorry for the hurt, pain and suffering caused by Aboriginal males to our wives, to our children, to our mothers, to our grandmothers, to our granddaughters, to our aunties, to our nieces and to our sisters.

We also acknowledge that we need the love and support of our Aboriginal women to help us move forward.

To assist, the men also called for community based violence prevention programs that are specifically targeted at men; the establishment of places for healing for Aboriginal men; resources for rehabilitation services for alcohol and drug problems; and better support for literacy and numeracy for Aboriginal men and linking of education to local employment opportunities. I am unaware whether there has been any response to this call - despite the request that there be so by September 2008.

I have every confidence that Indigenous communities – supported by government – can own the problems that exist in their communities and more so, that they want to own the problems.

For governments, you have to stop seeing Indigenous people as problems and recognise our role as the solution brokers to the problems that debilitate us.

For Aboriginal communities the challenges is to seize back your role in determining your futures; determine what measures are needed in your community to ensure the basic functioning of the community.

Recognising the first nations status of Indigenous Australians

Finally, the other piece of the puzzle to ensure adequate human rights protection in Australia revolves around the recognition of the status of Indigenous Australians as the first peoples of this land.

We have never come to terms with what this means in a comprehensive or holistic manner. Instead, we have dealt with those aspects of our shared history that have emerged from time to time – such as native title – by treating them as impediments and seeking to overcome them.

In the coming years we will jointly face other major challenges that threaten our way of life as Australians – such as access to water resources and dealing with the impacts of climate change. The traditional knowledge of Indigenous peoples and the traditional lands and waters and custodianship practices of our peoples will have a key role to play in dealing with these issues. So they provide another opportunity to consider the important place of Indigenous peoples within our society.

We should address these issues alongside outstanding issues relating to the colonisation of the country and outstanding issues of land justice, reparations and addressing the entrenched inter-generational poverty and trauma that still exists.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples will provide us with an important tool in how we could move forward in this way.

The Declaration highlights that we have failed Indigenous peoples for centuries and that one of the contributing factors for this has been the lack of support for Indigenous peoples’ collective characteristics. This is not about special status, it is about maintenance of identity and ensuring that cultures that – in most countries – are vulnerable to exploitation and are marginalised, are not lost with the full human tragedy that goes with that loss.

It is a very positive, aspirational document that sets out ambitions for a new partnership and relationship between Indigenous peoples and the nation states in which they live. For example:

It affirms that indigenous peoples make a unique contribution to the diversity and richness of civilizations and cultures, and promotes cultural diversity and understanding.

It explicitly encourages harmonious and cooperative relations between States and indigenous peoples, as well as mechanisms to support this at the international and national levels.

It is based upon principles of partnership, consultation and cooperation between indigenous peoples and States. So for example, Article 46 requires that every provision of the Declaration will be interpreted consistent with the principles of justice, democracy, respect for human rights, non-discrimination and good faith.

I don’t recall seeing any public discussion of the Declaration that talks about it in this positive light or that recognises that it is fundamentally a document about partnership. Instead, the public discussion has been much more alarmist and negative in its tone.

Over the coming months and year we will see the government take two important steps for appropriate recognition of Indigenous peoples. First, they will formally endorse the UN Declaration as an appropriate framework to guide the relationship with Indigenous Australians. And second, they will support the establishment of a national Indigenous representative body.

Both will provide impetus to reconfiguring the relationship with Indigenous peoples based on respect for our cultures and with a view to entering genuine partnerships with us. This will challenge many Australians. And it will provide the opportunity for us to deal with longstanding, unfinished business.

Conclusion

I have offered my comments tonight to both provoke and to stimulate. And hope that I have offered them constructively and in a spirit of reconciliation – and to honour the legacy of the great Charlie Perkins.

When asked about his legacy in 1994, Charles Perkins said:

I'm here today, gone tomorrow, and I've only just played a small role like other Aboriginal leaders do, but we're only passing, you know: ships in the night really. And where the answer lies, is with the mass of Aboriginal people, not with the individuals.

Addressing the continuing non-recognition of our rights, and dealing with the consequences that flow from that non-recognition, is the true challenge of our age. And I urge you tonight to recognise that the journey that Charlie undertook, that great ride to Freedom, still continues today.

Please remember, from self respect comes dignity, and from dignity comes hope.

Thank you