1 September 2016, Athenaeum Theatre, Melbourne, Australia

Every day we hear grim and grimmer news that suggests we are passing through the winter of the world. Everywhere man is tormented, the globe reels from multitudes of suffering and horror, and, worst, we no longer know with confidence what our answer might be. And yet we understand that the time approaches when an answer must be made or a terrible reckoning will be ours.

Perhaps this is what BuzzFeed meant when it featured an article with the title ‘Ten Shitty Alternatives to Drinking Yourself to Death’.

And in our age of clickbait – where our supposedly best newspapers feature articles such as ‘Six Hot Mini Skirts Not To Wear to Your Father’s Funeral’, ‘22 Photos To Restore Your Faith In Humanity Without You Actually Having To Do Anything To Help Improve It.’, ‘Top Five Crimes Favoured By Bilbies That Look Like Bilbies’, or the almost as endearing ‘Ten Ozzie Heroes Who Should Get A Fucking Medal’.

The last, I must admit, gives rise to a nagging question. Are the featured ten to be gonged for heroism or for copulation? There are enough holes in this for a One Nation senator to sense a NASA conspiracy.

In any case, in such an age my first thought was that I should get with the program, using vapid cliches like “get with the program”, and share with you my top ten Tasmanian novels.

Why?

Because these books were the ones in which I first discovered my world and myself. In them I discovered why writing matters.

Why, you may wonder, Tasmanian and not Australian?

And the seemingly sacrilegious answer is that I don’t believe in national literature per se. I do believe in Australian writing, conceived mostly in obscurity, frequently in poverty, almost always in adversity. I believe in that writing as important, as central, and as necessary.

But that’s a different matter from a national literature. Nations and nationalisms may use literature, but writing of itself has nothing to do with national anythings – national traditions, national organisations, national prizes – all these and more are irrelevant. National anythings imply responsibilities, morals, ethics, politics.

And writing, at its best, exists beyond morality and politics. It is at its most enduring when, like a bird, or a beach, or a criminal bilby, it is completely irresponsible, committing the top five crimes favoured by writers that look like writing.

Meat may be murder but so too for a thousand years were books – one sheep or goat for every eight pages of vellum made from their skin. Gutenberg’s revolution wasn’t simply one of swapping a scribe’s calligraphy for machine-pressed type. It was also swapping this highly expensive vellum for cheaper paper made out of rags; and within half a century – most importantly, most revolutionary of all – of swapping the Latin of the rulers for the vernacular of the ruled.

That had many consequences, not least for the impetus it gave to the Reformation, the growth of science, of the Enlightenment, of democracy. It also fed powerfully into a new idea of a people bound by a language which evolved into the profoundly modern idea of a nation-state bound together not by religion and monarch but by the common speech.

And the signet ring common speech needed was literature. With the rise of the nation-state we witness as its necessary corollary those new figures, the national poet and, later, the national novelist, and the national literature they purportedly embody. A language is not, as is often claimed, a dialect with a navy. A nation though is a dialect with a literature.

And yet, that same literature is not a nation. It is not reducible to kitsch ideas like national spirit, nor is it bound by borders. A writer belongs both to the homeland of the people they love and to the universe of books, and can never renounce either.

This leads to the great paradox of national letters – writers who seem rooted in the particular but whose works are deemed universal. Arguably the greatest German writer of the 20th century was Franz Kafka, who was, of course, Czech. His tales of alienation, of guilt, of not being what you seem, could perhaps only have been written by a German-speaking Jew who grew up in a Catholic Slavic city like Prague. But what that makes Kafka – German, Jewish, Czech, Slavic – is perhaps not the point. He is a writer being true to the multitudes within himself that are one and many.

“Germany? But where is it?” asked Goethe and Schiller in a book of poems they co-authored in 1796. “I don’t know how to find my country.”

Who of us does?

Goethe, the greatest of German writers – the writer who, it has been said, invents not just German literature but Germany – finally found the realisation of his dream of Germany and with it his inspiration to break with the stifling dead hand of French literature on German writing in the work of an English playwright, William Shakespeare.

I say English, because until the ascension of James I to the throne in 1603, Shakespeare himself wrote for only one of the four countries that then comprised the British Isles, England, and was deeply concerned with Englishness. But after 1603, and the consequent union of Scotland and England to form the nation of Britain, Shakespeare consciously became a British writer.

In Shakespeare’s Elizabethan plays the word England appears 224 times, while the word Britain is used only twice. After 1603, the word England only appears 21 times in his Jacobean plays while the word Britain now appears 29 times. The word English, used 132 times under Elizabeth, is only used 18 times under James. The word “British” was never used by Shakespeare at all until James came to the throne.

Shakespeare, like language itself, could be both things, neither thing and anything. His writings, in turn, were heavily influenced by Italian writers such as Petrarch and Boccaccio, and the French essayist Montaigne. In some ways their poetry and essays were more a fixed lodestone for him than the territory claimed by his monarch, a movable feast that prior to his birth had included much of France, and by his death incorporated the distant country of Scotland.

The history of letters is then a history of transnational ideas, styles and revolutions, which when they achieve fashion become celebrated and misrepresented as the reactionary virtues and stagnant spirit of nations.

It is ironic, then, that at the moment Australian writing began to announce itself as a force in the world, that at the moment it became perhaps our dominant indigenous cultural form, there ceased to be very much about it that might fit the thin idea of a national literature.

And that, to my mind, is no bad thing.

The corrupting notion of the great American novel is just one example of the end result of such empty thinking – books so huge that, like large plastic bags, they ought to be issued with warnings of death by asphyxiation if you take them to bed to read.

For over a century Australia wanted a national culture like those that had come to define European nations in the 19th century. The result was a mostly dreary colonial monoculture writ small in the image of the Melbourne and Sydney middle class. Caught between an imperial publishing culture that saw Australia as a consumer of English books but not a producer of writing on the one hand; and, on the other, the earnest nationalist expectations that there be some distinctly singular Australian voice led to a mostly moribund culture of thin confusions – Jindyworobaks on the one hand, a cringe towards Anglo modernists on the other.

And then, from the late 1960s, at the very moment globalism takes off, so too does Australian writing. This paradox – which you may have thought would lead to the death of any Australian writing – instead finally liberated it from the old nationalist arguments. Though the dead hand of the old intelligentsia lingered on in academia and literary journals, it was finished. Australian writing began to flourish, and at its best it wasn’t a recognisably national literature in the European mould.

There isn’t and there doesn’t have to be a single united national project linking Benjamin Law to Tim Winton, that seeks resonances between Helen Garner and Omar Musa, that demands continuities between JM Coetzee and Alexis Wright. What matters is that we have these writers and their works in all their diversity, and so much more besides. And if we are freed of having to make a case for national worth or national failure in our books, so much the better. Writers are, after all, not the Australian swimming team and we don’t need missives from John Bertrand to make us feel better in the eyes of the nation.

Were, though, we to take the measure of whether Australian writing matters by what our political leaders think, we may feel a little like a Rio garage owner after Ryan Lochte visited. One simple piece of maths illustrates this point.

In 2014–15, our government spent $1.2 billion to keep innocent people in a state of torment and suffering so extreme it has been compared to torture. This destruction of human beings is deemed a major priority by our country, and is supported by both major parties. In the same year, the same government spent a little less than $2.4 million on direct subsidy to Australian writers, the sum of whose work it may be argued, whatever its defects and shortcomings, adds up to a collective good.

These figures are worth pondering. What Australia is willing to spend in one year to create a state-sponsored hell on earth for the innocent is what Australia would spend in 500 years supporting its writers. It may be worth considering as a cure for the chronic poverty of Australian writers, that in order to be 500 times more valuable to the nation than they presently are, that writers practise – instead of word processing – offshore processing, by aiding, abetting, participating in and covering up acts of rape, murder, sexual abuse, beatings, child prostitution and suicide. Writers then would have a wholly admirable case to put to government for state sponsorship and political protection.

Who knows? Our prime minister might even turn up at a writers’ festival in a hi-vis jacket, a foie gras smear in jaffa icing. Would he be so moved by what he hears and sees as to put $5 in our begging bowl?

But I am not in begging mood. A writer may be fated to failure, poverty, slander, incomprehension and critical columns by Andrew Bolt. But a writer lives standing up, and they die kneeling. I am not arguing a case for more state support of writing. Heaven forbid that writers – who create wealth for others, jobs, and the only good news Australia seems to get these days internationally – should have any claim on the public purse – unlike, say, a failing, unprofitable and rigged entertainment like the Olympics.

But it is worth us pondering – if only for a moment – the question as to why our political class has such hostility towards writing. It may be that there is, buried in here, an inverse compliment: that Australian writing matters enough to power for power to want Australian writing to vanish for serving an economic purpose that doesn’t accord with an economic ideology.

Bill Henson recently said the cultural cringe was back in Australia. I fear the situation may be worse than that. After all, the term cultural cringe denotes respect if not for our own culture then at least for culture from other countries. But what if the end consequence of neoliberalism is a contempt for anything that can’t be measured by money and status? What if there is no interest in any culture no matter what country it comes from? When art and words exist solely as power’s ornament, compliment and cover?

For in our post-fact, post-truth, post-reason world, words seem to ever less correspond with the world as we experience it – as if the world itself is not what we experience but what power tells us we must accept as reality.

As Karl Rove put it, about the Bush imperium in 2004, laying out the case for a new way of perceiving the universe, “when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality – judiciously, as you will – we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out.”

In this view, reality is expressly the realm of power, and the rest of us become asylum seekers camped on its borders, reduced to wordless observers. Rove’s prescient words could have been an instruction manual for Donald Trump, for Boris Johnson, for Pauline Hanson, for every Twitter troll and transnational marketing executive.

And in the face of this coming wave, it matters more than ever that we have ways of reconciling the experience of our lives with that of the larger world – a world in which we find false words are routinely used by power to deceive, dissemble and disempower. It matters that there might be a society where some are allowed the possibility of questioning, of not agreeing, of saying no, of proposing other worlds, of showing other lives.

It matters that there be voices in society speaking of what exists outside ideologies, that acknowledge both the beauty and the pain of this life, that celebrate the full complexity of what it is to be human without judgement, that aspire, finally, to give our lives meaning.

It is not that literature should prosecute a case or carry a message. It is that at its best it does neither. At its best it escapes the conventional categories of ideology, convention, taste and power, it subverts and questions and dares to rebel.

And though I didn’t know it at the time, all this was implicit in the first Tasmanian novel I ever read, and the first of my top ten Tasmanian novels. I discovered it at the age of 12 in a book spinner at my high school.

The high school I was at had been built for a large housing commission suburb. It was violent, and the violence was unpredictable. One boy put a pair of scissors through another’s hand. Another boy rammed a chisel up another’s anus. A boy and his mate would take pot shots at kids walking home from school with an air rifle. Gang beatings were commonplace. It had a name as the worst school in Tasmania. I am not sure if it was, but it wasn’t a pleasant place.

On my third day at the school, in first year, I was sitting with two newly made friends on a bench seat hung off a brick wall, and we were eating our lunch. Some older boys walked by, including their gang leader, a stocky, powerful youth already sprouting sideburns. He halted, turned to us, and asked one of my new friends what he’d just said.

My friend had said nothing and said so. The stocky boy came over, leant in, and with a movement I now understand must have been learnt, gently cupped the boy’s chin with his palm, almost a caress, before slamming the boy’s head back, as hard as he could, into the brick wall three times. As the stocky boy turned and went to walk away, my other friend cried out, “Why?” The stocky boy turned, smiled, and said, “Because I can.”

My world was never quite the same. It was far from the worst violence I would witness, but being the first it left its mark. Violence, I saw, didn’t need a reason. And nor in that school where bullying and violence were endemic was it accountable. The teachers sought to maintain a rough order, not mete out justice. And over my four years at that school I came to see that, much as I hated it, this violence was also both a protest and an assertion of something deeply human; that the violence, sickening, despicable and damaging as it was, was also a strange assertion of freedom by people who had very little free agency.

I am not sure why I picked that book out that day. I remember the book was very thin, and that this made it seem an attractive prospect. I had been an avid reader until that time, but all that I read avidly were comics seasoned with some science fiction and a box of old penny Westerns. In contrast, the novel I had picked up was very strange to read. It was the first adult novel I ever read and it had an indelible impact. If I didn’t understand much of what it was about, that was also the way of much of the adult world that stood before me in all its enchantment. Rather than its impenetrable mystery making the book less compelling for me, it made it more so.

Reading Wuthering Heights, Dante Gabriel Rossetti observed, “The action takes place in Hell, but the places, I don’t know why, have English names.”

My experience with Albert Camus’ The Outsider was not dissimilar: the characters have French names and the places an Algerian geography, but the action and spirit, were, it was clear to me, entirely Tasmanian.

If I didn’t understand much of Camus’ The Outsider, Meursault’s killing someone because of the heat made perfect sense to me because it made sense of the world I lived in. I understood the lack of judgement at the book’s heart. I sensed the emotional damage that existed beyond what for a 12-year-old was the novel’s incomprehensible philosophy, because many of my friends at that school were odd and missing in ways that felt akin to Meursault. And I understood – only too well – the danger of telling the truth, which leads to the execution of Meursault. For I had learnt the imperative of lies.

I understood a man who lives through his senses in a sensual world, who lives for the beach and the sea and is undone by the heat of the sun, because my world – a child’s world – had been a similar world, of beaches, of light, of heat, and also, in my case, of rainforested wild lands and rivers where I had spent my childhood.

Above all, I intimated one thing that excited me like nothing else: strange and alien as only a book like that could be to a 12-year-old, it also felt true to something fundamental. To life. And to my life. And that was a truth I had never before experienced in books.

None of these ideas, it is fair to say, were to the fore in my copies of The Phantom, or Sun Sinking, Apaches Dawning.

Later I would discover much more about Camus that made him even more the quintessential Tasmanian writer I had sensed him to be from the beginning but had not fully known. Camus was not a Parisian intellectual. Coming from Algeria he was himself the outsider, a man from what was viewed as a colony, who nevertheless did not view his world and his origins as less. He celebrated the beach, the sun, the world of the body and its pleasures.

Camus entered the European tradition of the novel at the moment when a 19th-century idea was at its most powerful, the idea of history as destiny. But it was an idea in which he saw implicit the dangers of totalitarianism. To that idea he opposed the idea of the natural world. “In the midst of winter,” he wrote, “I found there was, within me, an invincible summer.”

In Camus’ writings I found my experience of Tasmania’s rivers and forests, its great coasts and beaches, made sense of. They were what I had felt them to be: something inseparable; a world that lived in me and was indivisible from me unless I allowed it to be taken. Camus would later write that “brought up surrounded by beauty which was my only wealth, I had begun in plenty”. And that beauty and plenty I had known in my life, and the name of it was freedom.

“The misery and greatness of this world: it offers no truths, but only objects for love,” Camus wrote in his journal. “Absurdity is king, but love saves us from it.”

I was going to continue to list my other top Tasmanian novels, to show how I discovered other aspects of my Tasmania in each one, and how through their words I saw why writing matters. I was going to say how their worlds were already mine, and everything I read was everything I had already lived; that I passed through the writing of their books to the other side where there was some understanding and some reconciliation that was also a form of love for what my world was and for what all our worlds are. How it was as if, reading those books, I passed through the mystery to the truth, only to discover behind the truth an ever greater mystery.

I was going to tell you about so many Tasmanian writers – Cortázar, Márquez, Baldwin, Carver, Lispector, Rosa, Bolaño, and Chekhov. I wrote pages on the wonderful talk of Bohumil Hrabal’s great novels; on the incomparable Faulkner and the shock of visiting his hometown in Mississippi, which until I smelt the dust and felt the heat and saw the kudzu I had not realised was also American. I was going to talk of Borges and his joyous pride in books being reality and a dream, and that dream the only reality worth living for, and how those games with time and chance were the same games played in the stories I grew up with. I was going to talk of Kafka and Conrad and Tolstoy and Hašek. I was going to talk, I came to realise, for several days and still not be done for it was, in the end, not a talk I was writing but a memoir in books.

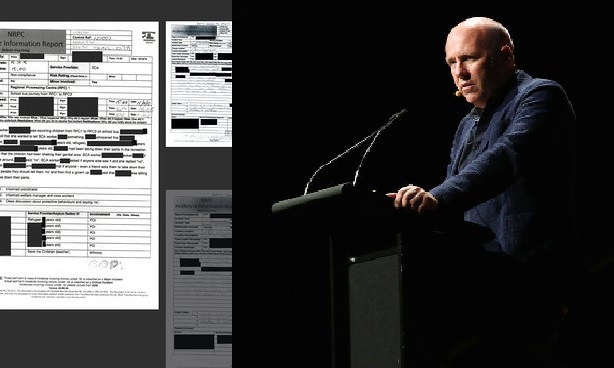

And then I stumbled upon an extraordinary trove of anonymous Australian short stories. It was the most moving Australian writing I had read for some long time.

All around us we see words debased, misused and become the vehicles for grand lies. Words are mostly used to keep us asleep, not to wake us. Sometimes, though, writing can panic us in the same way we are sometimes panicked at the moment of waking: here is the day and here is the world and we can sleep no longer, we must rise and live within it.

This writing has woken me from a slumber too long. It has panicked me. The stories are very short, what might be called in another context “flash fiction”. Except they are true stories.

I suspect they will continue to be read in coming decades and even centuries when the works of myself and my colleagues are long forgotten. And when people read these stories, so admirable in their brevity, so controlled in their emotion, so artful in their artlessness – their use, for example, of the term NAME REDACTED instead of a character’s actual name to better show what is happening to a stranger is not an individual act but a universal crime – then, I suspect, their minds will be filled with so many questions about what sort of people Australians of our time were. Let me read a handful to you. If you want to read them yourself, go to the Guardian website where these are published, along with 2000 others.

28 April 2015

At about 2129hrs … [NAME REDACTED] approached staff in RPC3 area [NUMBER REDACTED]. She began to vomit. A strong smell of bleach was detected. A code blue was called. IHMS medical staff attended and [NAME REDACTED] was transported by ambulance to RPCL for further treatment … At 2220hrs IHMS informed control that as a result of their assessment it appears that [NAME REDACTED] has ingested Milton baby bottle sterilizing tablets.

28 Sept 2014

I was asked on Friday (26-9-2014) by a fellow teacher [NAME REDACTED] if I would sit with an asylum seeker [NAME REDACTED] who was sobbing. She is a classroom helper for the children … She reported that she has been asking for a 4 minute shower as opposed to 2 minutes. Her request has been accepted on condition of sexual favours. It is a male security person. She did not state if this has or hasn’t occurred. The security officer wants to view a boy or girl having a shower.

12 June 2015

I [NAME REDACTED] met with [NAME REDACTED] in [REDACTED] at RPC 1 … During the course of the conversation [NAME REDACTED] disclosed that she had sex while in the community and that it had not been consensual.

CW asked [NAME REDACTED] if she had told anyone about this, [NAME REDACTED] stated that she had not told anyone other than CW that it was not consensual including IHMS. She stated that she did not tell IHMS that it was “rape” as she did not want “lots of questions” and if she said it was rape there would be “lots of questions’. [NAME REDACTED] stated that she told the man “no, no, no” and that the only man she wanted to have sexual relations with was her husband … the incident occurred during Open Centre and the man was Nauruan.

3 Sept 2015

[NAME REDACTED] was crying and was observed to be very shaken … [NAME REDACTED] reported that a Wilsons Security guard had just hit him. [NAME REDACTED] explained to [NAME REDACTED] that he was in tent [REDACTED] with [NAME REDACTED], [NAME REDACTED] and [NAME REDACTED] when a security guard entered and yelled at them, “hey are you in here?”. [NAME REDACTED] then reported that the security guard grabbed him around the throat and hit his head against the ground twice. [NAME REDACTED] also said that the security guard threw a chair on him … [NAME REDACTED] asked [NAME REDACTED] to show her who the security guard was. The children lead CW to area 10 and pointed at a male security guard … [NAME REDACTED] said “he hit me”. [NAME REDACTED] then asked [NAME REDACTED] “why did you hit me?”. [NAME REDACTED] then moved towards [NAME REDACTED] and in a raised voice responded “did you come in here, you are not allowed in here, get out of here”. [NAME REDACTED] then lead the children out of area 10.

2 December 2014

At approximately 1125 hours I was performing my duties as Whiskey 3.3 on a high watch in Tent [REDACTED] was alerted by an Asylum Seeker that female Asylum Seeker [NAME REDACTED] was trying to hang herself in Tent [NAME REDACTED]. I immediately responded. On arrival I saw [NAME REDACTED] holding [NAME REDACTED] up. [NAME REDACTED] appeared to have a noose around her neck. I called for a Code Blue straight away. I then assisted [NAME REDACTED] by untying the rope while [NAME REDACTED] held her and we took [NAME REDACTED] and placed her in the recovery position.

29 May 2015

[NUMBER REDACTED] yo male was on a whiskey high watch from a previous incident … [NAME REDACTED] grabbed an insect replant [sic] bottle and started drinking a small amount of its contents. CSO grabbed [NAME REDACTED] by the shoulders while his PSS offsider removed the bottle from [NAME REDACTED]’s hands. [NAME REDACTED] sat down and began sobbing over the incident.

15 January 2015

I CSPW [REDACTED 1] was speaking with [REDACTED 2] on the grass above the security entrance of Area 9. [REDACTED 2] informed me that her husband [REDACTED 3] had reported 4 months ago to her that he had been in a car with his [NUMBER REDACTED] year old son with 2 Nauruan Wilsons Security officers, [REDACTED 2] stated that according to [REDACTED 3], [REDACTED 4] was sitting in-between himself and the security officer. [REDACTED 2] stated that this car was taking the two from Area 9 to IHMS RPC3. [REDACTED 2] alleged that [REDACTED 3] informed her that their son [REDACTED 4] had said to [REDACTED 3] that one Nauruan officer had put his hand up [REDACTED 4’s] shorts and was playing with his bottom. [REDACTED 3] … removed [REDACTED 4] from the middle of the car and placed [REDACTED 4] on his lap but did not say anything as he feared the two Nauruan officers in the car with him … [REDACTED 2] informed me that approximately five months ago a [REDACTED 5] Officer had ran his hand down the back of her head and her head scarf and said to her “if there is anything you want on the outside let me know. I can get you anything.”

26 June 2014

[REDACTED 1] informed SCA caseworker that his partner [REDACTED 2] tried to commit suicide by overdosing on medication pills. [REDACTED 1] stated that the couple changed rooms without permission – there were some family pictures on wall of old room and [REDACTED 2] was trying to rip them off the plastic wall. Wilsons guard came into room and tried to stop [REDACTED 2] from damaging property. [REDACTED 1] stated Wilsons officer then stepped on her son’s picture, kicked them and told them to shut up. It was following this that she got upset, went to her room and took the pills.

5 May 2015

On morning bus run [NAME REDACTED] showed me a heart he had sewn into his hand using a needle and thread. I asked why and he said “I don’t know” … [NAME REDACTED] is [NUMBER REDACTED] yrs of age.

27 Sept 2014

Witnesses informed CM that a young person had sewn her lips together, one of the officers [REDACTED 1] had gone to the young person’s room to see her. The officer then went to his station with other officers and they all began laughing. Witnesses approached the officer asking what they were laughing about, the officers informed witnesses that they had told a joke and were laughing about it. Witnesses then stated that the young person’s father had approached officers the next evening seeking an apology from officer [REDACTED 1] for laughing at his daughter. The young person’s father at this time was informed that the officer [REDACTED 1] was at the airport, allegedly this is the reason the father then went and significantly self-harmed.

There is a connection between me standing here before you and a child sewing her lips together – an act of horror to make public on her body the truth of her condition. Because her act and the act of writing share the same human aspiration.

Everything has been done to dehumanise asylum seekers. Their names and their stories are kept from us. They live in a zoo of cruelty. Their lives are stripped of meaning. And they confront this tyranny – our Australian tyranny – with the only thing not taken from them, their bodies. In their meaningless world, in acts seemingly futile and doomed, they assert the fact that their lives still have meaning.

And is this not the very same aspiration as writing?

In the past year, what Australian writer has written as eloquently of what Australia has become as asylum seekers have with petrol and flame, with needle and thread? What Australian writer has so clearly exposed the truth of who we are? And what Australian writer has expressed more powerfully the desire for freedom – that freedom which is also Australia?

That is why Australian writing is the smell of the charring flesh of 23-year-old Omid Masoumali’s body burning himself in protest. The screams of 21-year-old Hodan Yasin as she too set herself alight. Australian writing is the ignored begging of a woman being raped. Australian writing is a girl who sews her lips together. Australian writing is a child who sews a heart into their hand and doesn’t know why.

We are compelled to listen, to read. But more: to see. The ancient Assyrians thought the footprints left by birds in the delta mud were the words of God to which there was a key. If the key could be found God could be seen. We need to use words to once more see each other for what we are: fellow human beings, no more, no less. To find the divine in each other, which is another way of saying all that we share that is greater than our individual souls.

I say “see”, but of course there are no images. There are only leaked reports, which contradict so much of what the government claims. If there was an image of a woman just raped, of the back of murdered Reza Berati’s bloody head – if there was just one image – just one – we would face a national crisis of honour, of meaning, of identity.

And though I wish I could, I cannot tonight speak for Omid Masoumali. I cannot speak for Hodan Yasin. I cannot speak for the unnamed who have tried to kill themselves swallowing razor blades, hanging themselves with sheets, swallowing insecticides, cleaning agents and pills, and then were punished for doing so. I cannot speak for that girl with sewn lips. I can only speak for myself.

And I will say this: Australia has lost its way.

All I can think is, this is not my Australia.

But it is.

It is too easy to ascribe the horror of what I have just read to a politician, to a party or even to our toxic politics. These things, though, have happened because of a more general cowardice and inertia, because of conformity. Because it is easier to be blind than to see, to be deaf than to hear, to say things don’t matter when they do. Whether we wish it or not, these things belong to us, are us, and we are diminished because of them.

We have to accept that no Australian is innocent, that these crimes are committed in Australia’s name, which is our name, and Australia has to answer to them, and so we must answer for them to the world, to the future, to our own souls.

We meekly accept what are not only affronts but also threats to our freedom of speech, such as the draconian Clause 42 D of the Australian Border Force Act, which allows for the jailing for two years of any doctors or social workers who bear public witness to children beaten or sexually abused, to acts of rape or cruelty. The new crime is not crime, but the reporting of state-sanctioned violence. And only fools or tyrants argue that national security resides in national silence.

A nation-sized spit hood is being pulled over us. We can hear the guards’ laughter; the laughter of the powerful at the powerless. We can hear the answer made all those years ago in a schoolyard as to why one human could hurt another being made again, the real explanation of why the Australian government does what it does.

Because it can.

“All I can say,” Camus wrote in his great novel, The Plague, “is that on this earth there are pestilences and there are victims – and as far as possible one must refuse to be on the side of the pestilence.”

For our country’s vainglorious boasts of having a world-leading economy, of punching above its weight, of having the most liveable cities and so on are as nothing unless it can bear this truth. We can be a good nation or a trivial, fearful prison. But we cannot be both.

There is such a thing as a people’s honour. And when it is lost, the people are lost. That is Australia today. If only out of self-respect, we should never have allowed to happen what has.

Every day that the asylum seekers of Nauru and Manus live in the torment of punishment without end, guilty of no crime, we too become a little less free. In their liberation lies our hope. The hope of a people that can once more claim honour in the affairs of this world.

For Camus, resistance was the heroism of goodness and kindness. “It may seem a ridiculous idea,” he writes, “but the only way to fight the plague is with decency.”

Camus understood moments such as Australia is now passing through with asylum seekers not as wars that might be won, but aspects of human nature that we forget or ignore at our peril.

“The plague bacillus,” Camus writes, “never dies or vanishes entirely … it waits patiently in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, handkerchiefs and old papers, and … the day will come when, for the instruction or misfortune of mankind, the plague will rouse its rats and send them to die in some well-contented city.”

We in Australia were well-contented. But now the rats are among us; the plague is upon us; and each of us must choose whether we are with the plague, or against it.

A solidarity of the silenced, a resistance of the shaken, starts by weighing our words, by calling things by their proper names, and knowing that not doing so leads to the death and suffering of many.

It is by naming cruelty as cruelty, evil as evil, the plague as the plague.

The role of the writer in one sense is the very real struggle to keep words alive, to restore to them their proper meaning and necessary dignity as the means by which we divine truth. In this battle the writer is doomed to fail, but the battle is no less important. The war is only lost when language ceases to serve its most fundamental purpose, and that only happens when we are persuaded that writing no longer matters.

In all these questions I don’t say that writing and writers are an answer or a panacea. That would be a nonsense. But even when we are silenced we must continue to write. To assert freedom. To find meaning.

With ink, with keyboard. With thread, with flame, with our very bodies.

Because writing matters. More than ever, it matters.

Thank you.